Because it is proported to be about emotions I have been looking forward to getting my hands on the new book out of the Harvard Negotiation community Beyond Reason: Using Emotions as you negotiate by Roger Fisher and Daniel Shapiro. It’s pretty good, which is a relief, since most books about emotions written by rational intellectual people are crap.

It is not without flaws. It is padded out with a review of the ground covered in the other books from their branch of the negotiation community. I was surprised by a disconnect – emotions are very powerful but the advice the book gives is very temperate. For example, it is good thing to find common ground with your partner. Discover shared hobbies! Yes, might oak trees of good relationships from from such tiny seeds, but this kind of advice follows in the tradition found in most geek written books when they touch on emotion: excessive distancing and reductionism.

Having gotten that out of the way – the structure of the book is just marvelous. I was particularly delighted that they don’t fall into the tedium of enumerating a hierarchy of emotions.

Here’s the nut. Humans have some very core concerns: to find a fulfilling role for example. If these core concerns are not being met then strong negative emotions will follow. If they are met, strong positive ones will rise. Skilled negotiators entice the positive emotions out, and avoid baiting the negative ones. Their reward: productive flexible creative problem solving sessions.

I particularly liked that they complement each core concern with a verb; so here they are:

- Appreciation – which is expressed.

- Affiliation – which is built.

- Autonomy – which is respected.

- Status – which is acknowledged.

- Role – which is chosen and fulfilling.

While this book is written with negotiation in mind – i.e. an episodic attempt to engage in collaboration – these issues clearly arise across the spectrum of collaborative effort. That list is universally actionable!

For example: a manager should keep a score card for every participant v.s. each of the five core concerns. By participant I mean individuals and groups. For example each of your suppliers. Then act on that, encourage action to improve each item. Do that using those verbs. If you can’t answer the question “How is X chosing an fulfilling his role?” your not doing your job. (I might add to that list: “What is the top idea in X’s mind?”)

All this has triggered a number of insights. For example notice: if you struggle and win a particular role there is the risk that there will be negative emotions created – because winning is not choosing. Fun, eh?

Notice how role and status are pulled apart here. I hatz how often they are treated as synonymous. Notice that instead of using the term loyalty they use the terms affiliation and autonomy. I’ve written before about the dual nature of assuming a role, e.g. that there is something you do and something others do. By example, you can’t lead if nobody follows. By teasing out status from role they address that duality.

I’m pleased that they don’t talk about loyalty. Loyalty is a outcome, and so it is built indirectly. But also loyality is a term of hierarchical organizations; where roles are not chosen they are assigned and status is not acknowledged it is merely painted on the door.

Is affiliation just another name for what I call common cause in community dynamics? A binding force of the collaborative effort, like gravity. People get very emotional about it! Which is why they guard the public goods of their communities so emotionally, with scolding, patriotism, loyalty oaths, etc. etc.

Autonomy sounds a lot like freedom, something people get emotional about. Freedom depends on a rich pool of public goods. Which are created thru communities of common cause. Autonomy is to freedom like club good are to public goods. This is a book about negotiation; as you negotiation your always attempting to frame up a new club. Even if the negotiation is something as trivial as creating a link in the supply chain.

Business jargon likes to talk in terms of power: supplier power, consumer power. It’s a pain to be a buyer when the supplier has all the power, and via versa. If you have a single supplier for a key component, for example funding, then that supplier will be powerful. All five of those aspects illuminate why that’s an emotional situation. If you have billions of tiny customers then no one of them has much power and the emotions change, they become more alienated. There is something deep running thru the dynamics of all exchange networks that these five issues can help to inform.

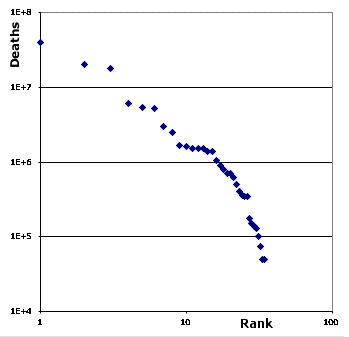

This is another addition to my collection of data about things that have a powerlaw in distribution. This one shows major conflicts of the 20th century and uses deaths/conflict as a measure of their intensity. In a sense this is a continuation of the distributions shown in an earlier posting that

This is another addition to my collection of data about things that have a powerlaw in distribution. This one shows major conflicts of the 20th century and uses deaths/conflict as a measure of their intensity. In a sense this is a continuation of the distributions shown in an earlier posting that