Cities are a geographic solution to the matching problem. Want to find a spouse, a model train caboose, a slide rule, a bar were they play music but not too loud, huitlacoche? At the same time cities aggregate webs of links that last over time. These networks of links sustain the urban residents and attract the rural. Economically vibrant cities like Silicon Valley or New York furiously generate new links. They build on top of the deep complex mesh of existing links. Economically weak and declining cities sputter along creating a fewer new linkages while their underlying networks are hoarded, decay, or depart.

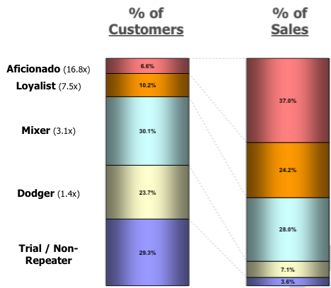

The term social capital was introduced a few decades back in an attempt to give a name to some of that. The original idea of social capital was that you could sum up the value of a person’s connections if you sum up the capital equipment they had access to thru those connections. For example if I can borrow a hammer from my neighbor that’s part of my social capital. If I can borrow the company’s trunk when moving my apartment then that too is part of my social capital. If the boss will lend me his plane in crisis that part of it too.

Events that make and break links add and subtract from the net worth of your social capital. While you may lose a lot of capital worth when your house burns down you can lose a lot more when you move between cities, exit a club, switch proffessions, graduate from college.

There is a picture in today’s paper that show how people in the Astrodome have put up huge signs in an attempt to find other people in their social network. It says they ring a bell each time one link is reconnected. It boggles the mind to imagine what’s involved in re-stitching the social web of an entire city. How would I ever reconnect with the butcher that makes my sausages?

The demand to recreate these connections is one of the reasons why we will rebuild something around New Orleans. The desire to reclaim the social capital is extremely strong. It will work in tandem with the necessities of the physical capital. New Orleans is a distribution bottleneck for a whole range of goods. Distribution bottlenecks are very analogous to cities; a web of supply mets a web of demand and flows thru them like the food flows thru Paris.

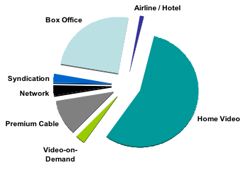

One feature of New Orleans economy is how capital intensive it’s distribution flows are. It’s not like New York, Boston, or Silicon Valley where the goods that are flowing are practically weightless. The oil, grain, cement, automobiles that flow thru New Orleans depend of extremely expensive installations. Consider Henry Hub where the price of natural gas futures is fixed; 15 natural gas pipelines that reach out across the entire nation and a sea of storage tanks. Or consider the refineries any one of which would take Billions of dollars to reproduce. Or the oil terminal where one pipeline carries 20% of the US oil ashore. These distribution networks are very hard to move. Moving Howard’s Hub would require rerouting all those major pipelines.

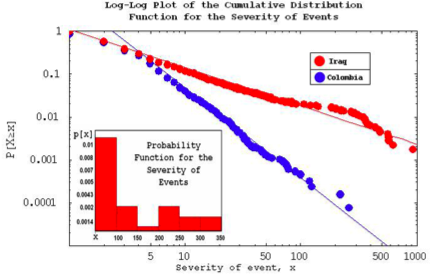

The nodes and links in both the social and the physical networks range across various key metrics. Their value for example. My neighbor’s hammer is less valuable than my employer’s truck. Their resistance to breaking. Moving a pipeline is harder than changing where a shipping container goes.

When the hurricane comes it strips all the leaves from the trees; when the flood comes the weakest links are dissolved. But these are the vast majority of the links; and so that it always the greatest loss. It is very hard to imagine that those billions of dollars we are spending on relief and rebuilding will be focused on regenerate those. Yesterday I read about the engineer asked about the environmental effect of pumping out the city and he said; we have higher priorities right now. New Orleans has always been a city with a severely skewed wealth distribution. This is only going to make is worse.