One of the ways to get a El Curve is to take a population and iteratively reward the winners slightly in each round. This appears to be the model that gives rise to power law distributions in things like oil reserves. So I’m always interested in research that looks at the details of the iterative process in the vicinity of a system that exhibits an El Curve. Income for example.

From Brad DeLong

Very nicely done: very much worth reading:

Sam Bowles and Herb Gintis (2002), “The Inheritance of Inequality,” Journal of Economic Perspectives.

That really is a marvelous paper beautifully and carefully written. Fascinating.

I did not know that back in the 1960s there was a consensus that the data showed America to be the land of opportunity, i.e. that your parents’ caste did not tend to dictate your own. I gather from this paper that this was wrong due to an assortment of errors in the design of the studies.

Today we know that if you’re born poor your chance of rising is small; the poverty trap. if you’re born rich your chance of dying poor is small. The authors think it’s unlikely that this second syndrome will come to be called the affluence trap.

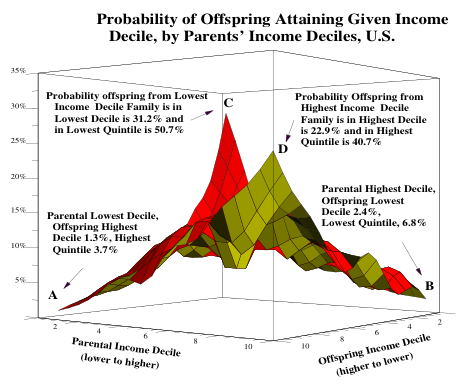

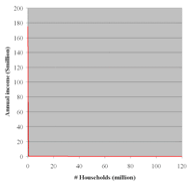

Under some definitions of fair the maximally fair society would give each child an equal chance at various levels of income. In American society if your parents had high incomes chances are your income will be high. A child born of parents in the top 10% has a 40% chance of ending up in the top 20%. If your parents were dirt poor then it’s very unlikely you will have a high income. Children born into the bottom tenth have a 3.7% chance of getting into the top 20%.

The paper includes this great peice of eye candy. This shows the chance a child will fall into a given 10% of the income range given his parents’ position in that range. The two peaks are the poverty/affluence traps.

The fun thing about the paper is the very careful attempt they make to tease out of the data some information about the causality of the intergenerational income status trap. The extent of the trap is really amazing. If you average income over 15 years then the correlation is .65. That means there is a 65% chance that the next generation’s income will be within 1 standard deviation of the previous ones.

Of course what one wants to know is what’s the causal chain from one generation to another. For example maybe the key driver of wealth is a sense of humor (though i doubt it) and parents tend to pass that on to their children a bit by nature and a bit by nurture. The nice thing about the paper is that they make a really substantial effort to draw out of the data as much causality as possible. This is almost impossible since there are plenty of causal chains for which the data is very very thin.

Of course all this stuff is very tangled. Wealthy parents tend to buy more schooling, for example. The trick is to condition the results so you’re getting a reasonably pure contribution from each stage. I.e. so if you doubled the schooling without changing the parent’s wealth your model would predict accurately what the change in outcome would be. That’s really hard. For example it’s common to use data about twins or brothers to try and tease out the differences between nature and nurture. But even that’s very subtle. For example we know the height is very tightly tied to genetics but we also know it varies tremendously depending on how well people are eating. We know that brothers tend to have very similar incomes, unless you partition the data by race at which point you discover that black brothers are extremely highly correlated and non-blacks much less so. They do a beautiful job of stepping thru this mine field.

Here are the numbers they manage to pull out of the data:

- 4% IQ

- 7% Schooling

- 12% Wealth

- 2% Personality

- 7% Race

The key result of the paper is that 32% of the trap remains unexplained. It’s something else. Humor say.

I still have an affection for my five ways to get rich model (pick the rich parents, spouse, pocket, card, or trade).

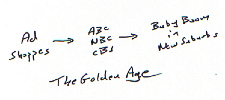

To hear tell in the golden age of advertising little shoppes of advertising artisans lined the streets of Manhattan. As the curtain rises, desperate mouthwash manufacturing mogels would travel to this village and step into one of these shops. He would, of course, be carrying a few million dollars. In the second act the shop owner would craft a campaign and place it on the three television networks. In the third act the American public would tune and discover they had an unfulfilled desire to gargle more. As the curtain goes down they are all placing bottles of mouthwash into their shopping carts at the A&P.

To hear tell in the golden age of advertising little shoppes of advertising artisans lined the streets of Manhattan. As the curtain rises, desperate mouthwash manufacturing mogels would travel to this village and step into one of these shops. He would, of course, be carrying a few million dollars. In the second act the shop owner would craft a campaign and place it on the three television networks. In the third act the American public would tune and discover they had an unfulfilled desire to gargle more. As the curtain goes down they are all placing bottles of mouthwash into their shopping carts at the A&P. Distribution channels fascinate me. Part of my fascination is the way they are fundamentally two faced; the distribution firm must balance between two strong forces. So an entertainment/advertising channel is trying to find a balance between the desires of it’s advertisers and the desires of it’s audience. Actually it’s got three faces, which is even more fun, but let’s gloss over that today. This tension is the ecology within which these butterflies evolve.

Distribution channels fascinate me. Part of my fascination is the way they are fundamentally two faced; the distribution firm must balance between two strong forces. So an entertainment/advertising channel is trying to find a balance between the desires of it’s advertisers and the desires of it’s audience. Actually it’s got three faces, which is even more fun, but let’s gloss over that today. This tension is the ecology within which these butterflies evolve. For example consider this first image which is becoming the

For example consider this first image which is becoming the

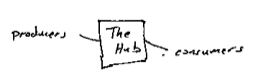

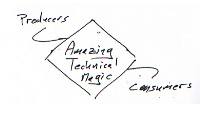

Between producers and consumers you need to insert some sort of exchange, a trusted intermediary. I’ve always liked the way that people draw this as a cloud. It suggests angels are at work, or possibly that if you look closely things will only get blurry and your glasses will get wet. Even without getting your self wet things aren’t clear even from the outside. For example what do we mean by trust? Does it mean low-latency, reliability, robust governance, low barriers to entry, competitive markets, minimal concentration of power – who knows?

Between producers and consumers you need to insert some sort of exchange, a trusted intermediary. I’ve always liked the way that people draw this as a cloud. It suggests angels are at work, or possibly that if you look closely things will only get blurry and your glasses will get wet. Even without getting your self wet things aren’t clear even from the outside. For example what do we mean by trust? Does it mean low-latency, reliability, robust governance, low barriers to entry, competitive markets, minimal concentration of power – who knows? There are some leading design patterns for working on these problems. Sometimes the cloud condenses into a single hub. For example one technique is to introduce a central hub, or a monopoly. The US Postal system, the Federal Reserve’s check clearing houses, AT&T’s long distance business are old examples of that. Of course none of those were ever absolute monopolies; you could always find examples of some amount of exchange that took place by going around the hub – if you want to split hairs. Google in ‘findablity’, eBay in auctions, Amazon in the online book business are more modern examples.

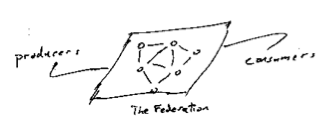

There are some leading design patterns for working on these problems. Sometimes the cloud condenses into a single hub. For example one technique is to introduce a central hub, or a monopoly. The US Postal system, the Federal Reserve’s check clearing houses, AT&T’s long distance business are old examples of that. Of course none of those were ever absolute monopolies; you could always find examples of some amount of exchange that took place by going around the hub – if you want to split hairs. Google in ‘findablity’, eBay in auctions, Amazon in the online book business are more modern examples. Federated approachs are clearly more social than hubs. In markets where the participants are naturally noncompetitive they can be quite social. For example when national phone companies federate to exchange traffic, or small banks federate to clear checks or credit card payments. That can change over time, of course. The nice feature of a federated architecture is that it helps create clarity about where the rules of the game are being blocked out. How and who rules the cloud is part of the mystery of trust.

Federated approachs are clearly more social than hubs. In markets where the participants are naturally noncompetitive they can be quite social. For example when national phone companies federate to exchange traffic, or small banks federate to clear checks or credit card payments. That can change over time, of course. The nice feature of a federated architecture is that it helps create clarity about where the rules of the game are being blocked out. How and who rules the cloud is part of the mystery of trust. The magic based solutions have great stories or illustrations to go with them. For example the early Arpanet architecture had each node in the net act advertise it’s service to it’s neighbors who would then shop for the best route – boy did that not work! I worked on on three multiprocessors in the 1970s that had varing designs for how to route data between CPU and memory. One of these, the Butterfly, had a switched who’s topology was based on the Fast Fourier Transform.

The magic based solutions have great stories or illustrations to go with them. For example the early Arpanet architecture had each node in the net act advertise it’s service to it’s neighbors who would then shop for the best route – boy did that not work! I worked on on three multiprocessors in the 1970s that had varing designs for how to route data between CPU and memory. One of these, the Butterfly, had a switched who’s topology was based on the Fast Fourier Transform.

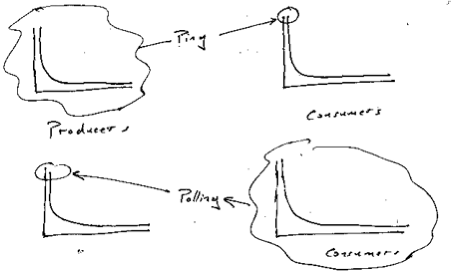

when they have fresh content. This is sometimes called the Ping problem. Sometimes it’s called push, to contrast it with the typical way that content is discovered on the net i.e. pulling it from it’s source. The problem interests me for an assortment of reasons, not the least of which is that it’s a two sided network effect. On the one side you have writers and on the other side you have readers. I draw a drawing like the one on the right for situations like that. Two fluffy clouds for the producers and the consumers connected thru some sort of exchange.

when they have fresh content. This is sometimes called the Ping problem. Sometimes it’s called push, to contrast it with the typical way that content is discovered on the net i.e. pulling it from it’s source. The problem interests me for an assortment of reasons, not the least of which is that it’s a two sided network effect. On the one side you have writers and on the other side you have readers. I draw a drawing like the one on the right for situations like that. Two fluffy clouds for the producers and the consumers connected thru some sort of exchange.