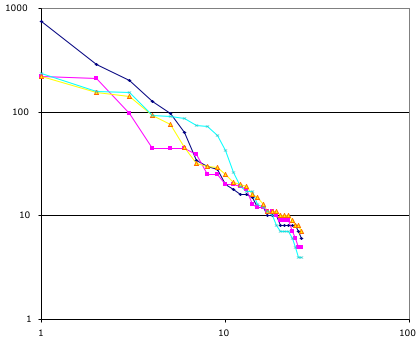

The frightening aspect of these power-law distribution is how destructive to equality they are. If you are engaged in a game who’s over arching process tends to create these skew’d distribution your and your love ones are very unlikely to go home a winner. For example in the other day’s distribution of open source licenses 81% of the projects have been awarded to the top two licenses.

But notice this! Games with a inequitable distribution of winners creates powerful incentives to form teams. Power-law games encourage group forming! A fascinating point since group forming seems to be a particularly good way to temper the severity of the inequality in these systems.

This posting on the power-law distribution in Oscar winning movies triggered that realization. The paper shows a powerful bandwagon effect around the various entertainment awards. Once a few dozen Oscars climb on the bandwagon of your film the rest are extremely likely to follow. For example the film Titanic captured huge numbers of awards one year. These award systems are interesting – they have lots and lots of prizes. For all I know there is an award for best costume designed for a fish.

So why would games like this encourage group forming? We know that common cause is the foundation of making durable groups. We know that teams in games have an obvious common cause – winning. Notice that if your game is like the Oscars then that bandwagon is the prize. The individual Oscars are only points.

Fascinating. Put your self in the shoes of our fish-wrap designer. Admit it, you desire an Oscar. If you can win an Oscar your set for life! Today you have two options. Should you go work on that absolutely marvelous art film “Hamlet the Haddock” or should you go work on Titanic? Oh, did I mention your children need shoes? Given the nature of the game and the imaginary box I just put you in you don’t really have any choice. Dump your vision boy, go work on Titanic! Your fish wrap master piece doesn’t stand a chance against the bandwagon Titanic.

Now I have a very bad attitude about contests. One winner many losers hardly sounds like a good design pattern, at least not for the players. So it’s a little disturbing to see that if your embedded in a game with power-law generating processes there are powerful arguments that direct you toward joining teams. Your best option is to sublimate your individuality and begin to form groups.

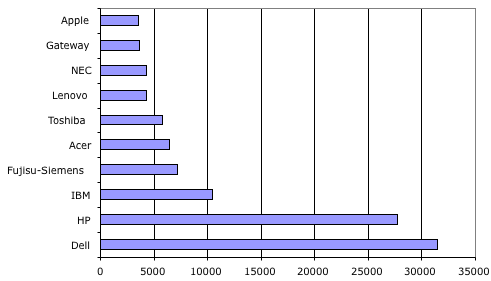

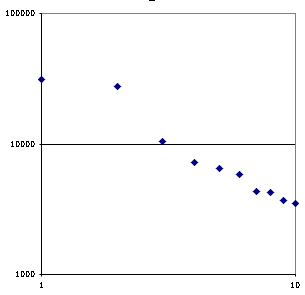

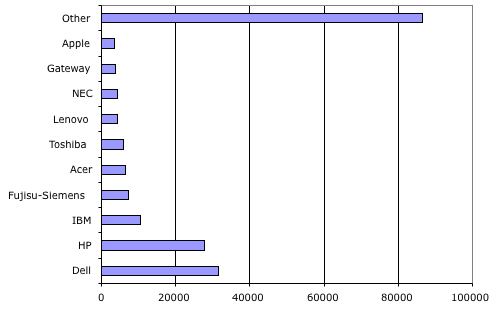

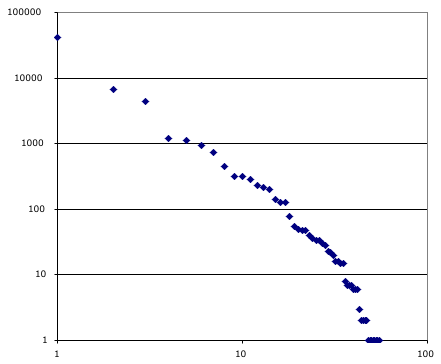

The chart at right has a dot for

The chart at right has a dot for