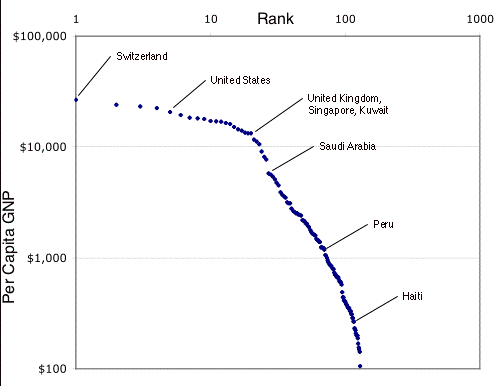

The top 1% own just about half of everything. That’s really hard to think about. Everywhere you look; half of that is owned by only 1% of the population. Cars, trees, radio, TV, bytes; half of all of it. Can that be good? Kevin Phillips new book talks about this in depth. The reviews are good, the interviews are interesting and I’ve been collecting links and interesting quotes from them:

Assorted reviews of Kevin Phillips’s book WEALTH AND DEMOCRACY: A Political History of the American Rich.

A review in New York Review of Books by Jeff Madrick. “the fabulous personal fortunes of the 1980s and 1990s now rival and in some ways even exceed the mythical fortunes of the Gilded Age.”

“Phillips then goes on to argue that such excesses of wealth and greed and inequity have helped bring down–or may even have been the chief cause in bringing down–virtually all flourishing great powers in the past”

Yale historian Paul Kennedy writing in the LA Times

Phillips writing in a

Q&A sidebar to that article: “Conservatives tried to make class conflict something to frown on in 1896 and 1932, but without great luck. The turning point came when the success of the New Deal greatly reduced the share of wealth and income going to the top 1%, and as democracy and a middle-class ethos carried into the 1950s and 1960s, “plutocracy” began to seem like an old threat that no longer existed. Now the concept of an economic “over-class” is as relevant again as it was in 1896.”

Bruce Reed’s review from Washington Montly “… a funny thing happened on the way to the class war: The rich won.”

From Princeton economist Paul Krugman’s editorial in the New York Times “an influential body of opinion has reacted to global warming and the emergence of an American plutocracy the same way: ‘It’s not true, it’s not true, it’s not true, nothing can be done about it.'”

Kevin Phillips, “Market Extremists Amok,” The American Prospect vol. 13 no. 13, July 15, 2002. Kevin sure can write a full scale rant. “Extreme politics, in this new form as in others before it, has a distinct regional home. As much as the ideological excesses of the left in the 1960s evoked Berkeley, and the militia groups on the right were a Rocky Mountain phenomenon, the market mania of the last two decades has centered on Texas — economic Lone Ranger country, where market fundamentalism and religious fundamentalism have joined to create a uniquely strident culture.”

Paul Magnusson’s review review in Business Week. “Phillips compares the U.S., post-September 11, to Holland in the early 1700s and Britain in the 20th century, when each nation, at the peak of its economic power, expended its energy and treasure in a burst of warfare.”

Phillips quoted from the transcript of Bill Moyers’ interview on PBS: “a dynasty is a dynasty is a dynasty and these problems are there, and this incredible amount of money is … is just staring this country’s historical role in the face ”

NPR interview (real audio) “a ten fold increase in wealth in seven years” for the top 400 in the nation; never before.

Audio interview (real audio) from Radio Nation. 47% of the nations wealth is in 1% of the population’s hands.

Amazon Editorial Reviews, Customer Reviews

Joe Conason’s review in

New York Observer writes: “What makes Mr. Phillips’ analysis so radical is his insistence on examining the roots of the great fortunes’and revealing the state power that underwrote so many of them.”

Price compairson: addall and abebooks. The author’s web site for the book.

Interview on Minnesota public radio.

Chapter One appeared in the Denver Post.

Diane Rehm’s interview from WAMU in DC.

KCET – Life & Times Town Hall SpecialTranscript. “In 1981, the average of the ten highest compensated corporate executives was $3.45 million. In 1988, the average of the ten highest compensated was $22 million. In 2001, the average of the ten highest compensated was $155 million. You know, that’s a 45-fold increase.” or “Middle fifth, the average household cash income in the middle fifth, sort of your medium household, $31,700 in 1979, $32,600 in 1989, $33,200 in 1997. Now we got to the top one percent, $256,000 in 1979, $507,000 in 1989, $644,000 in 1997.”

Article from LA times by Kevin Philips circa 2000. “In the 2000s, just as in the 1970s, the 1930s and the 1890s, a tough bear market and its aftermath could be what brings about an economic, governmental and regulatory overhaul. A serious stock-market decline always serves as a political as well as financial indicator. Brother bear–the Ursa Major of economic disillusionment–has been the power behind populist and progressive booms from William Jennings Bryan through Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

July 8th 2002 Article from The Nation Dynasties! by Kevin Phillips. “Only at first blush is there silliness to the idea of the United States–the nation of the Minutemen, John and Samuel Adams and Thomas Jefferson–becoming a hereditary economic aristocracy.”

Review by Scott London. ‘The growing ineffectiveness of American government is part of a larger “reversal of fortune” where political and economic influence has shifted from the grassroots of America to a new “guardian class” in Washington.’

Atlantic Monthly: A wordy dialog between James Fallows and Kevin Phillips.

Audio interview and call-in on The Connection, a radio program on NPR. “The top 10% own about 80% of the publicly traded stock.”

Kevin Phillip’s is one client of the Leigh Bureau. Here is his biography from their speaker’s catalog.