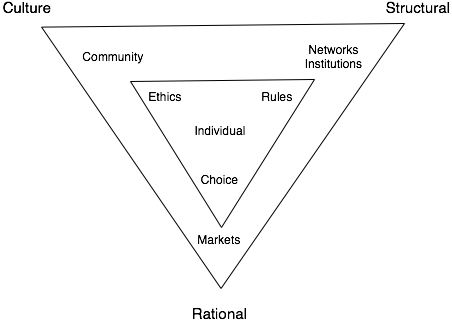

Because I’m interested in how standards emerge I have a few models in my noodle. The classic model is that the king tells everybody the rules and they obediently follow them. The institutional model is that powerful institutions act like little kings in their dominions and then negotiate with each other when necessary. The bottom up model holds that exchange standards emerge spontaniously from pairs engaging in exchange and then others mimic those behaviors until groups emerge with similar behaviors. These groups a little like institutions but since their governance tends to be very diffuse the accumulation of new members is more due to network effects and less transparent influencing devices than then top down commands.

The bottom up standardization is somewhat more interesting to me than the top down. Open Source for example tends to be a bottom up phenomenon, and the marketing of platforms and tool kits tends in that direction as well. The bottom up ones are also the common pattern as technology disrupts from below and suddenly large populations of new players enter a domain.

No surprise then that I’m reading the early chapters of Sync: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order by Steven Strogatz In these chapters he describes a model that he along with a colleague developed for explaining how a population of cells, insects, whatever might come to beat in sync. The model began with an observation that in a number of natural systems, fireflies and the heart’s pacemaker cells for example, fall into synch. If you look into the mechanism of individual cells they have an oscillator that generates a beat. That beat is the beat of the heart cells, the applause of a audience, the flash of the firefly.

If you get a dozen fireflies (actually you need south-east Asian fireflies) in a room and let them go they strobe rhythmically but randomly at first. After a bit they begin strobe in groups and then in a bit they all strobe in synch. What drives them into synch? Etymologists had figured out that some species fireflies react to the flash of other flies by advancing their oscillator while other species retard it just a bit. This slight coupling turns out to be enough to bring them all into synch.

That turns out to be all you need to get these system to synch. Well almost.

The proof is a very pretty thing.

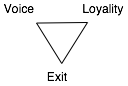

The first part of the proof is pretty simple. If two ossolators get into synch with each other that’s that. They won’t fall out of synch. They call that absorbtion. The individual cells, fireflies, etc. are absorbed into a group that all behaves the same. You can see now why I’m interested since that sounds like community or standards talk. The act of absorbtion is equivalent to the concept of sticky in a business model, or switching costs in a standards discussion.

The second part of the proof involves a beautiful bit of geometric thinking. If you have a set of fireflies, toilets, etc. You can make a geometric space with the firing time of one of the as the origin and for each otherone he’s off on one axis of your space some distance from that origin depending on how out of synch he is. The state of the system is then the point in the N space defined by those cell’s offsets from our favorite cell.

Now imagine that the system doesn’t synchronizes. That means there is some set of points in the N space that are “terrible.” Each time our favorite cell fires the state of the system moves to another point in the space. For these terrible systems they obviously just have to move from terrible point to terrible point. For my purposes such systems aren’t “terrible” they are just ” nonstandardized” system; or systems that fail to form groups.

They were able to prove was that whenever our favorite cell transforms the state of the system from one set (terrible or not) the new set is larger than the old set. Which, if you think about it for a moment, means that either all the points in the space are terrible, or none of them are.

It only works for certain kinds of lightly coupled rhythmic systems will come into synch, some won’t; but it doesn’t depend on the initial system state.

To see which kind come into synch and which don’t you need to visualize the inside of the blinker a little. Presumably inside the blinker some tension builds up until finally it triggers and the flash is emitted. You could plot tension v.s. time on a graph. Maybe it’s a straight line from start to finish. Maybe the tension rises fast at the beginning and then it becomes cautious and slows down before it goes pop. Or alternately it goes slow at first and then in a fit of enthusiasm it rushes into the blink. The systems that are start fast and then grow careful; those are the ones that synchronize. Because they spend a lot of their cycle type nearly triggered the little kick from the loose coupling is enough to push them over.

For my purposes, thinking about exchange standards (for example handshakes), then the repeating oscillation is the repeated application of the standard. Each time two people execute a coordinated handshake they are in sync. If other people observe that event and adjust their behavior a bit to increase their alignment with the ritualized handshake then you have a very similar system to the one described above. To get a curve shape similar to decelerate as you approach full – well I’ll admit I can’t quite see how that fits – but possibly the analogy is that exchange partners approach quickly at first but close the deal much more slowly.

Neat huh? Clearly is has something to says something about when groups and standards are more likely to form.

No King Required.