Here’s one of those b-school charts, this one about media reporting:

I the short days between when AI finally works and the Singularity clicks in we can imagine that metadata will tag all articles with this information.

I’ve only recently started reading Jay Rosen’s blog “Quote and Comment,” and I’m surprised that I like it. I generally find all the arguments about old/new media to be strangely pointless and hopelessly ill informed.

He draws our attention this wonderful Marshall McLuhan quote:

To start announcing your own preferences for old values when your world is collapsing and everything is changing at a furious pitch: this is not the act of a serious person. It is frivolous, fatuous. If you were to knock on the door of one of these critics and say “Sir, there are flames leaping out of your roof, your house is burning,” under these conditions he would then say to you, “That’s a very interesting point of view. Personally, I couldn’t disagree with you more.”

Exactly right. The arguments in the old media about old and new media are exactly of that kind. It must be exhausting to be modern media critic; to spending your days standing on that doorway having that conversation.

I haven’t read that much of Jay’s stuff yet. But one idea he toys with is that the media must to stop pretending to be dispassionate observers. They need to let go of the what I think he calls “the view from nowhere.” My imaginary tagging AI might do this for you – it might tag a report so you can know the presumptions and constraints of the reporter. That, for example he has deep intimate relationships with the institution he is reporting on and that these constrain his ability to be entirely transparent about what he knows; or – on the contrary – that he is an outsider likely to lack appreciation of the complex trade-offs the institution’s members are living within and thus likely to take cheap shots at their necessary hypocrisies. Or that the reporter is deeply invested in the current group consensus and often acts as a guardian of that consensus; e.g. that his primary loyalty is to his role and stature within that dominate consensus.

Of course we could imagine that something else, something other than my imaginary AI, might take responsibility for this tagging. Obviously there are lots of possibilities: ratings agency, a media critic (like Jay), the reporter himself, the blog sphere, … the possibilities are endless.

There is money in this. Everybody is slowly waking up to the commercial value in having increasingly accurate profiles of your counter parties. I have no doubt PR firms would pay a pretty penny for accurate profiles of the various entities in the media they must handle. And our AI tech is good enough already that it can do a pretty good job of this. Sadly, and typically, it is probably easier to make money on this by computing the profiles and selling them to a limited audience v.s. – say – Google doing it and then tagging everything.

This reminds me of an incident from back in the 80s. At the time there was an active small catalog industry. Once or twice a week the mailman would bring around another catalog full of stuff my household might want. Google used to have an awesomely fun search engine for scanned versions of these (toy) catalogs, they shut it down a decade ago; I assume small catalog industry shrank and moved online.

The mid-sized businesses that sent out these catalogs purchased mailing lists from vendors who had built models of each household/zipcode/region/etc. At some point a company, I think it was Lotus, brought out a product who’s intent was to empower smaller businesses to do this. The product came with a CD, and the CD had a simple profile for lots and lots of addresses. The idea being that the small business man would filter out a small targeted mailing list and send his catalog to those folks.

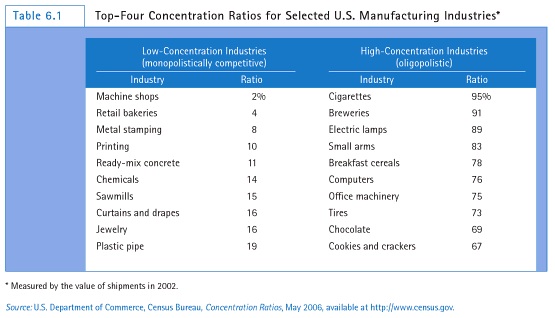

This was perfectly straight forward evolution in the technology of targeted marketing. It’s an information industry, so costs plummet. In information industries, what a big firm can afford usually quickly becomes something a small firm can afford.

What happened to this product? Outrage! People had no idea that this was going on, and they got very very angry. There was a little feeding frenzy in the press, and the vendor quickly withdrew the product. But of course, that did not stop the practice. It only left it in the shadows. To this day the targeted marketing industry still demands a veil of secrecy. The functional benefits of the “view from nowhere” voice as used in the media seems quite analogous; it provides a veil. I am not unsympathetic to the need for such compartmentalization.