Isn’t there is something unnatural about a venture capitalist who’s obviously a hard-core geek?

A long time back Tim Orton posted a list of links on systems that allow delegation of rights to other parties. I’ve been meaning to get around to writing about this kind of think because while lots of people tend to know about private/public key encryption and other approaches to the identity problem these methods seem to have been largely forgotten.

These are such a nostalgia trip for me. Back in the early mid 70s at CMU I had some light involvement in the development of a multiprocessor system known as C.mmp. One unique feature of the operating system of that toy was that it managed permissions using “capabilities” rather that “access control lists”. Capabilities are a much better design but nobody has ever really managed to make them very practical.

Access control lists, or ACL, protect things by marking objects with a list of who is allowed to access. For example if the question arises is Bob allowed to update the payroll data the ACL system works by checking a list associated with that data and then checking that the person about to make the change has proved he is Bob. ACL’s are like the guest list at an exclusive party, each time another guest shows up the doorman checks their ID against the guest list before letting them in. Maintaining the guest lists is a pain.

Capabilities allows Bob to delegate the task of updating the payroll to one of his acquaintances.

In a capability system Bob carries around a set of capabilities, think of them as like one of those huge key rings that building maintenance guys carry around. When Bob wants to modify the payroll data he pulls out the right key/capability presents it and the system checks it. If Bob want’s to delegate, he can hand the key to his assistant. Keeping all these keys under control is a pain.

Real world system work with a hybrid of keys and guest lists. In some situations you present an ID card (for example to withdraw books from the public library) and in other scenarios your provided with a key (for example when you rent a car).

One of the systems Tim points to is really just too cute: i.e. a programming language called E.

Most programming languages consist of a handful of tricks. For example one of Lisp’s trick is to bring the syntax and the parse tree so very close to each other so that at program build time you can do powerful transformations of your program. One of Python’s tricks is to leverage the source text’s indenting for syntax. One of Perl’s tricks is to weave a number of powerful micro-languages together into one dense rich stew. One of Erlang’s clever tricks is designing extremely light weight distributed tasks into the heart of the language.

E seems to have three key tricks. The most minor of these is that it stands on top of the Java VM. The second trick is to fold the idea of capabilities into the language. While in a traditional programming language you can manipulate an object if you can get a pointer to it in E you need to get the capability not the pointer. All kinds of clever cryptography is built in so that these capabilities enabling them to do clever things, like only work for an interval of time.

The last clever thing, the fun one, is an approach to multitasking based on “promises”. Rather than the usual collection of processes, micro-tasks, thread, locks, semaphores, queues, event handling, and messages that most languages cobble together in various combinations to create a multitasking system we get one construct; the promise.

Here is a very amusing description of why this might be “a better way(tm)”:

Let us look at a conventional human distributed computation. Alice, the CEO of Evernet Computing, needs a new version of the budget including R&D numbers from the VP of Engineering, Bob. Alice calls Bob: “Could you get me those numbers?”

Bob jots Alice’s request on his to-do list. “Sure thing, Alice, I promise I’ll get them for you after I solve this engineering problem.”

Bob has handed Alice a promise for the answer. He has not handed her the answer. But neither Bob nor Alice sits on their hands, blocked, waiting for the resolution.

Rather, Bob continues to work his current problem. And Alice goes to Carol, the CFO: “Carol, when Bob gets those numbers, plug ’em into the spreadsheet and give me the new budget,okay?”

Carol: “No problem.” Carol writes Alice’s request on her own to-do list, but does not put it either first or last in the list. Rather, she puts it in the conditional part of the list, to be done when the condition is met–in this case, when Bob fulfills his promise.

Conceptually, Alice has handed to Carol a copy of Bob’s promise for numbers, and Carol has handed to Alice a promise for a new integrated spreadsheet. Once again, no one waits around, blocked. Carol ambles down the hall for a contract negotiation, Alice goes back to preparing for the IPO.

When Bob finishes his calculations, he signals that his promise has been fulfilled; when Carol receives the signal, she uses Bob’s fulfilled promise to fulfill her own promise; when Carol fulfills her promise, Alice gets her spreadsheet. A sophisticated distributed computation has been completed so simply that no one realizes an advanced degree in computer science should have been required.

Very cute.

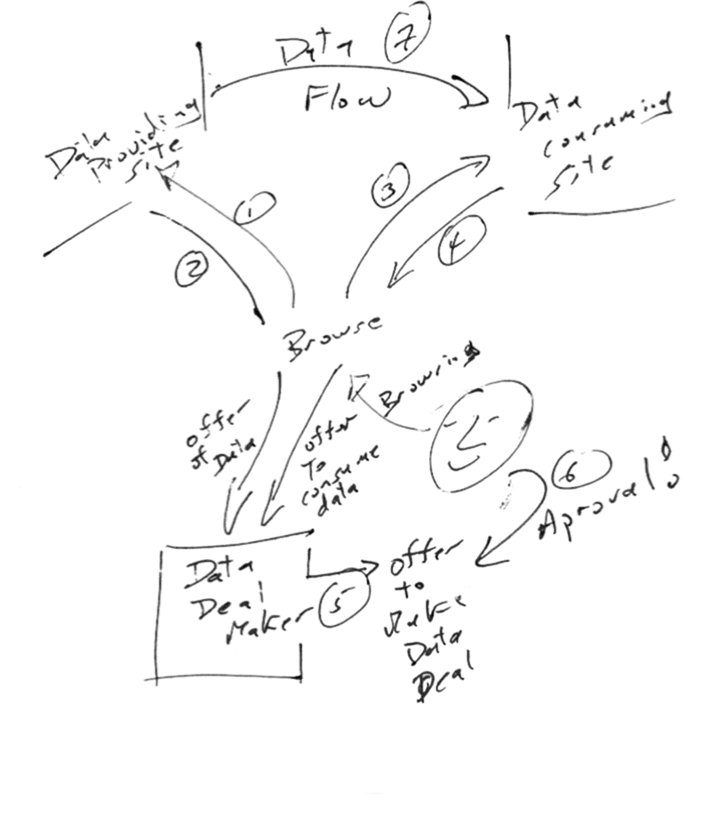

While I presume that Tim’s interest in all of this is so he can make, break, keep, and delegate responsiblity for promises with greatly increased efficency I suspect that it’s really just about money.

here (

here (