Category Archives: economics

Sense of Scale

One thing I’m finding particularly hard is getting a sense of scale for what’s unfolding in the markets, but here’s a run at the question.

Katrina was maybe a $80 Billion event, and it looks to me like Ike is probably a $30 Billion one. The Iraq war’s direct costs are probably 2 Billion a week. The 9/11 attacks destroyed about $16 Billion in physical assets, and the clean up cost about $11 billion; lots more in the ripple effects.

Microsoft, Apple’s, and Google’s market cap are roughly $230, $119, and $140.

AGI’s market cap a year ago was around $200 Billion, today it’s around 10. A year ago Fannie Mae, Lehman Brothers had market caps of was around $60 and $40 Billion each. That’s $300 billion total, about twice the size of the numbers in the 2nd paragraph.

These are big storms. With about 100 million households in the US, $300 Billion is three thousand dollars each.

These estimates are all aweful rough. I couldn’t quickly find estimates for the wealth distruction in the house markets, but here are a lot of write downs. Nate Owan takes a run at a similar question.

Tempering Moral Harzard Thru Mattress Design

In a great posting by Paul Kedrosky explains why the financial industry is just like a traditional mattress. Must educate those exuberant crony capitalists to abstain? Should chill the water bed? Ah platform engineering.

In a great posting by Paul Kedrosky explains why the financial industry is just like a traditional mattress. Must educate those exuberant crony capitalists to abstain? Should chill the water bed? Ah platform engineering.

Blow Up Rich

I’ve been trying to think about the financial structures around processes that exhibit highly skewed distributions. The insurance industry is a great place to find the examples. We buy insurance to hedge against the small but awful. Most of our houses don’t burn down, but it does happen. The chance of a fire is scale free, the insurance company protects it’s clients at the scale they care about, but who protects the insurance company against the rare event the burns down the entire town. There are three ways the insurance industry handles that scenario: they don’t cover it (excluding acts of god for example), they reinsure into a yet larger pool, or they avoid it by not insursing in certain venues. Over here at Bronte Capital is a posting arguing that Warren Buffet, who moved into the insurance industry in a big way over the last few years, has been working this third angle.

When process with a highly skewed distribution delivers it’s rare but powerful shock into the system, it’s black swans, everything designed to work with the median shocks is blows up. I’d be interested to know how the insurance industry handled the New England hurricane of 1938. I’d be interested to know how the insurance industry in Thailand handled the AID’s epidemic.

Another place I’ve been musing about exceptional, but inevitable, events is where you situate your career planning. I’ve a friend who likes to say that almost all the people he knows who made a fortune in their life “fell off a log into a pile of money” thru no special merit of their own except in some cases they consciously picked a good log to sit on. On the other hand a lot of people just fall off a log sooner or latter. It would be nice if, as you plan your career, you had a better sense of what the chances are in the trade you pick, in the economy at large. The fetish people have for presuming that career path probablities are entirely a matter of personal merit seem wreckless. I was quite impressed when an acquantance of mine with a degree in biology explained he was moving into lawyering because, well he didn’t put it this way, the climate was more predictable.

Recently I’ve been trying to explain how wily US cell phone pricing is. They sell monthly plans with N minutes and then when the exceptional crisis comes down the pike, you fall in love example, they charge you huge over charges. The typical plan delivers minutes at about five cents each and forty cents a minute. Better, at least for them, is that as little crissis come and go your start changing your plan to buy more minutes, which in the absense of a crissis you don’t use. That in turn raises the real cost of even you noncrisis minutes. It’s a very impressive pricing scam isn’t it! I recomend prepaid (t-mobile for gsm, pageplus for cdma on verizon).

If we ignore prepaid cell phone service, the cell phone contracts with a bundle of minutes every month are a bit like lousy insurance policies. You buy the option to use five hundred minutes, not because you need them, but because your insuring against the risk that you’ll run over and get stuck with the over charges. That’s great, and I mean that sarcasticly, they are selling you insurance against a risk they created.

It amuses me to wonder what would happen if everybody in the country could be coordinated into using all those free minutes one month. I very much doubt the phone companies can fufill that promise.

The options contracts implicit in those monthly cell phone contracts are analogous to the insurance pools. If we could coordinate the month of the phone it would be the analogous to a hurricane or a plague, at least from the point of view of the phone company.

That scenario has been playing out with the internet service providers, at least for the incompetent ones. For example Comcast sells me a package with certain assurances about what bandwidth I get into the Internet. Unsurprisingly the consumption patterns of their customers is highly skewed, and I’m one of the higher users since this site runs over that connection. Inspite of 20 plus years of history showing that Internet consumption grows extremely fast and quickly grows to fill the pipe provided Comcast was suprised when more users actually exercised the option they had bought. It is not relevant what these users are doing with the bandwidth (P2P, video, voice over IP, spam) because if it hadn’t been one of those it would have been something else.

This last example, the ISP’s problems, is not actually an example of pricing design in the face of a highly skewed distribution. It just looks like one at first blush. The real problem the ISPs face is the rapidly rising tide of usage. They thought they had a slower growing usage situation, something more like what is seen with the cell phones, but they were wrong. When they discovered some of the users were consuming all the bandwidth they thought they had purchased the ISPs presumed those users were little trouble makers rather than early movers. But that’s a mistake, soon everybody will consume all the bandwidth they can get.

Gridlock Economy

Michael Heller’s new book looks interesting. Heller was, for the last decade, been working to introduce a bit of balance into the discussion down stream from the idea that goes by the name “Tragedy of the Commons.” He originally called his idea “The Tragedy of the Anticommons.” Those who public goods coming to tragic ends often prescribe a dose of property rights. Heller is interested in situations where too many property rights create grid lock.

His Authors@Google talk is a good introduction. About a half hour long it touchs on various coordination failures with substantial social costs that arise from an abundance of property rights: Drugs that don’t get developed, families displaced from their legacies, urban development frustrated, air traffic congestion, foul ups in the post soviet privization programs. Good stuff, and he is reasonably straight forward about how societies should be more aware about the balance they strike when they architect their property rights schemes.

That last point is of particular interest to me, since it goes to the question of how you shape the power law curves. Is the single property owner who frustrates the urban developer the hero of the long tail; or is he just the worse case of ground cover strangling urban vitality? Guess I’ll need to read the book.

I’m bemused, or confused, by the realization that both these tragedies arise because some coordination problem blows up when too many parties have simultaniously have rights. I guess you might say the anticommons goes down the tubes when one player says no (or more often just lies silent) while the commons blow up when too many people say yes. After a bit I can’t see these as really different, it’s back to the group forming coordination problem.

The Triangle: Supply/Demand/Price

Back in school when I took economics 101 we would draw these curves showing that if you raise the price you don’t sell as much. In real life I’ve been surprised how rarely this seems to be true. In fact I’ve observed far too many cases where the price goes up and you sell more. Even more common are the cases where the lines are practically flat. I.e. the effect is very weak.

Back in school when I took economics 101 we would draw these curves showing that if you raise the price you don’t sell as much. In real life I’ve been surprised how rarely this seems to be true. In fact I’ve observed far too many cases where the price goes up and you sell more. Even more common are the cases where the lines are practically flat. I.e. the effect is very weak.

For example much is being made of the fact that miles driven has dropped by 3.7%. The price of gas doubled! Up +100%, down -3.7%

Now some of this is lag. So presumably there is a lot more pent up in the system as people adapt. But you’d think, wouldn’t you?

Markup

There is a lesson here:

Abstract. Individuals who are unaware of the price do not derive more enjoyment from more expensive wine. In a sample of more than 6,000 blind tastings, we find that the correlation between price and overall rating is small and negative, suggesting that individuals on average enjoy more expensive wines slightly less. For individuals with wine training, however, we find indications of a positive relationship between price and enjoyment. Our results are robust to the inclusion of individual fixed effects, and are not driven by outliers: when omitting the top and bottom deciles of the price distribution, our qualitative results are strengthened, and the statistical significance is improved further. Our results indicate that both the prices of wines and wine recommendations by experts may be poor guides for non-expert wine consumers.recommendations by experts may be poor guides for non-expert wine consumers.

From: Do More Expensive Wines Taste Better? : Evidence from a Large Sample of Blind Tastings

You should pay me to buy your wine, scrap off the prices and replace them with tasty robust high price labels.

Overdue Homework

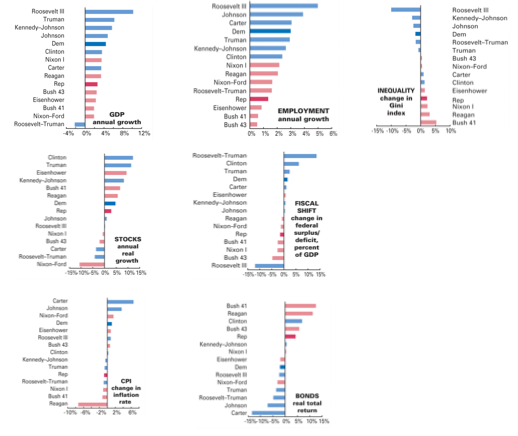

We have known about these charts for a while now; i.e. there is a sharp difference between how the economy changes under Democratic v.s. Republican presidents. The economists have apparently made no real progress on explaining why.

Note how the cartoon Republican, i.e. the cigar smoking plutocrat, apparently votes against his interests.

Only $69.95!

What are you worth? The Bush EPA thinks we are worth $6.9 Million each. 10% less than the Clinton EPA. No doubt that makes lots of regulations less, ah, necessary. I want to assure you; I think you are worth a lot more than that.

Meanwhile I gather that boffins think that a 10% rise in fuels prices drops the highway deaths by 1%; or in other terms that 4$ gas will reduce highway deaths by a thousand a month.

Oh boy. Arithmetic: 12 months a year; 1,000 deaths a month; $6.9 Million/person … or $82.8 Billion a year. That’s just the deaths of course, no doubt the injuries, loss of capital equipment and other costs mean we can multiply that by a another 3. With around a 100 million households in the US, and 365 days in the year that’s $6.81 per household per day. Feel free to spend the savings on gas.

On the other hand some people think these numbers are just numerology.

Stamp Scrip

During the depression people hoarded cash with great vigor. Prices were falling. Employment was uncertain. it made sense to wait, if you could. And so, the velocity of money plummeted. Transactions deferred are equivalent to idle economic capacity; i.e. this kind of hoarding is codependent with a depression. Money is like oil in the economic gears, Drain it out, the machine ceases to turn over. When the economic machine seizes up the puzzle is how to keep the oil in the machine. Add more and the participants will just horde that as well.

During the depression people hoarded cash with great vigor. Prices were falling. Employment was uncertain. it made sense to wait, if you could. And so, the velocity of money plummeted. Transactions deferred are equivalent to idle economic capacity; i.e. this kind of hoarding is codependent with a depression. Money is like oil in the economic gears, Drain it out, the machine ceases to turn over. When the economic machine seizes up the puzzle is how to keep the oil in the machine. Add more and the participants will just horde that as well.

During the depression there were multiple experiments with trying to force the money out of hiding, to increase it’s velocity. For example: a village might issue scrip dollars, say by paying their employees with scrip. This scrip can be converted at any time to real currency at 3% less than it’s face value; or at full value after a year. So far this is just a local currency. The next bit is the clever part.

This scrip requires some maintenance. Once a week, on Tuesday at noon, you have to affix a stamp to the dollar note, and these stamps cost a penny. This creates an incentive to spend the bill quickly, so as to avoid the chore of affixing the stamp. There are stories of towns reborn after this kind of scrip was introduced; i.e. where entire area’s economy machine had ground to a halt and apparently all that was needed was to find a way to force the oil to stay in the machine. These notes and stamps are a currency with a negative interest rate. These schemes are a local version of the macro economic trick of adjusting the interest rate to control the unemployment rate. I.e. you lower the interest rate to force idle currency into use as it’s owners seek a better return. There is a nice little book, a pamphlet really, written in 1933 about these schemes. You can read it online: “STAMP SCRIP” By Irving Fisher (Professor of Economics, Yale University). It has some fun stories in it.

Charles Zylstra, the enterprising man who first introduced Stamp Scrip to America (in a small western town) tells this story. A travelling salesman stopped at a hotel and handed the clerk a hundred dollar bill to be put in the safe, saying he would call for it in twenty-four hours. The clerk, whose name was A, owed $100 to B and clandestinely he used this bill for the liquidation of his debt, thinking that before the expiration of 24 hours he could collect $100 from his own debtor, whose name was Z. So this 100 dollar bill went to B, who, greatly surprised, used it to pay his own 100 dollar debt to one C, who (equally surprised) . . . and so on, and so on, all the way down to Z, who, with much pleasure, returned the bill to A, the clerk, who, in the morning, restored it to the salesman. And then did A, the clerk, stand petrified with horror to see the salesman light a cigar with it. “Counterfeit,” said the salesman, “a fake gift from a crazy friend, Abner; but he didn’t put it over, did he?”

Many failed attempts to add money to the system using scrip are mentioned, but many failed because they didn’t include this trick with the stamp. This story is full of lessons:

In Evanston, Illinois, it was a merchants’ association that inaugurated the Stamp Scrip. They inscribed it with a new word: “Eirma.” This is composed of the initials of the organization name: “Evanston Independent Retail Merchants Association.” In this long title, the word “Independent” expresses the motive for the scrip; for what the merchants meant to be independent of was the shopping in Chicago instead of Evanston and at the chain stores which had invaded their territory. They thought they could, by an appeal to town loyalty, prevent the scrip from circulating among their rivals. Accordingly, after getting a sufficient number of consents, they printed $5000 worth of “Eirma” and “sold” it to the members according to their respective requirements – for paying their employees and dealing with one another. In other words, the local members put up a guaranty fund of $5000 which was held in escrow by a bank. Fifty stamps, at 2 cents, retired the scrip, which was to he redeemed by the “Eirma” organization. In this instance the banks in general did not cooperate. The bankers’ motive of loyalty to a municipal enterprise was lacking. Neither did the town offer to receive the scrip for tax payments. Nevertheless the town lent its moral support, as the result of a very ingenious bid which was made by the Eirma organization. It so happened that the town’s own finances were in such poor shape that it had been obliged to defray some of its expenses by means of “tax anticipation warrants,” later redeemable by the town in cash. So the Eirma organization agreed to buy these warrants with the cash proceeds of the stamps as fast as these should be sold.(1) Thus, when the redemption date should arrive, for the Eirma the redemption would have to be effected with the initial guarantee fund, not with the proceeds of the stamps. This would leave the tax anticipation warrants still in the Eirma treasury for distribution to the members according to their purchases of stamps. The net result, therefore, of the Eirma dollars amounted to a purchase on the instalment plan of tax-anticipation-warrants, by the members of the Eirma Association. But in Evanston there crops out the first unfortunate result of copying the Hawarden precedent (of making the stamps affixable, not at set intervals, but with each transaction). Evanston is a larger place than Hawarden, so that it is not so easy in Evanston to detect the small disloyalties of the citizens. Accordingly the chain stores made a flank attack on the local merchants by agreeing with their patrons to receive the scrip, without stamps, provided the patrons would receive them back without stamps. Therefore, at last advices, the stamps were not selling as they should. The Eirma organization now concedes the superiority of dated scrip, and would like to pass the whole enterprise over to the municipality.

It would be interesting, but I’m not quite able to yet, build the ties between these schemes modern private currency systems, i.e. things like gift cards, airline miles, and coupons. Some have the goal of increasing transaction rates, and some hope to decrease it. Clearly airline miles and gift card issuers are happy if the transactions never happen. Coupons, like the one I got from Paypal/Ebay for a 10% discount (CPPJUNE0810P good only for 7 days), are intended to increase the rate. These effects are disjoint from the localization/loyalty goals of such micro-currency schemes. Could you create a Internet payment system along these lines? Now that would be quite a hack! See also vendor selling old scrip notes, and a nod to John.

See also: Demurrage