I’m still chewing on the idea of guard labor, so a pile of random thoughts I’ve been having.

Businesses adapt the ratio between guard labor v.s. productive labor. That ratio varies across firms within industries, from one industry to another, and inside of firms from on department to another. Presumably there is a great deal of peering over the walls. A lot of monkey see monkey do as people search for a different balance. For example if the neighbor organization appears more successful and they don’t spend time on daily progress reporting and your organization does then you might be tempted to jigger things; reducing the ratio of guard to productive labor.

The work done by labor shifts. It can shift into automation or codified processes and procedures. If the neighbor is using an elegant status board your organization might be tempted try that out. In effect shifting guard labor into automation. Processes and procedures are a capital investment. How you depreciate and retire them feeds directly into organizational agility. If a neighboring organization appears to be successful by setting aside their rule book and replacing it with a charismatic manager then you might try that. In effect shifting automation into guard labor.

If you cast this in an exaggerated light you’ll notice plenty of opportunity for polarization. For example guard labor may fall into the bad habit of talking up how lazy the productive labor is; not because they dislike the productive labor but because it helps to justify their role (talking their book). Same thing happens for al the pairs; e.g. X v.s. automation and other roles like customers and suppliers. Most organization players flirt with the guilty pleasure kind of such exaggerated behaviors. It’s worth noting that there is plenty of opportunity for similar polarizing behaviors to be found the variability across departments, between firms, etc.

Automation (or processed and procedures) means that productive labor can be highly guarded even in the absence of guard labor. The assembly line worker’s role is extremely guarded, by the machines that surround him. In that scenario the guard labor ratio is low, with say only one supervisor for a a dozen production workers. So how guarded work is somewhat independent of how much guard labor is involved. Mechanical turk workers might be a example of an outlier in that space – highly guarded work with very minimal guard labor.

It is a challenge to label the axis for how guarded labor is. One extreme might be labeled slavery, bound labor. At the other end we might expect to find labor that is enjoying very high values of achieving the people’s core concerns (appreciation, autonomy, affiliation, …). There are plenty of things that can bind labor: salary; stock options; roots in the firm or locality; specialized skills; lack of other options. In the Americas importing slaves from Africa was more effective v.s. enslaving the natives, I presume because natives had the option of running away.

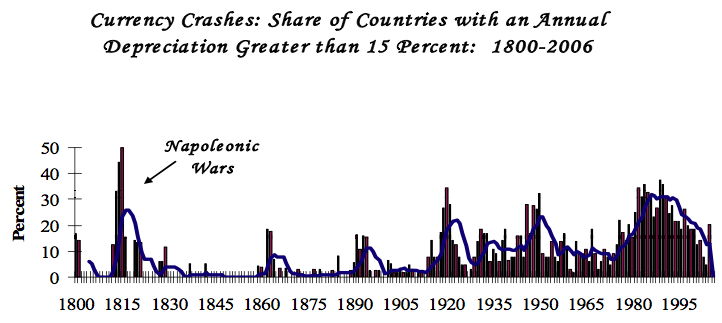

Like all costs the cost of guarding can internal or externally born. One point the paper makes is that unemployment acts as a kind of systemic guard. Obviously unemployment insurance acts to temper that effect. If incidences of unemployment tend to be short in duration, that also tempers the effect. The paper suggests that Italy, with high unemployment and low guard labor ratio, might be an example of an economy where the cost of guarding has been externalized. In this mindset taxing firms that tend to have high labor turn over is a Pigovian or pollution tax and helps to encourage the guarding to move in house where it will be on the books.

This posting about slavery is interesting to mix up with the guard labor meme. It’s all a bit rough but there are two rolls of the economic dice mentioned there that encourage the rise of slavery. Let’s decide that what we mean by slavery is state sanctioned and enforced slavery. Not that the other cases aren’t interesting.

The first scenario is the case where owners have land, but labor is scarce. The scarcity of labor means that the cost of owning slaves is lower than the cost of paying them a salary on the open labor market.

The second scenario is high demand for some good. I don’t entirely understand this suggestion; but i find it plausible. If I replace high demand with high volume it begins to make sense. If some labor intensive good is produced at very high volume an large industry will emerge and scaling effects will kick in. That will trigger the search for both the balance of guard to productive labor, the codification of process. In time the nature of the productive labor will become increasingly guarded. The guard labor ratio will rise – the absence of either automation, or technological schemes for assuring the productive labor adheres to the processes. In the extreme case that high ratio will lead to introducing slavery.

Of course you’d also need to be able to implement the bondage. So if the labor can run away, as in the early American colonies, it maybe a lot harder – even with the help of the state and cultural sanction and enforcement. Labor can also run away if you have a diverse economy; so it would seem to me that both these scenarios are much more likely and possibly even require homogeneity – a company town.

The first scenario suggest that in any case where labor becomes scarce the incidence of binding devices will rise. So when labor is scarce during the second world war and wages are capped employers introduce health insurance, which has turned out to be a very effective binding device. It is exaggerated to suggest most of these are equivalent to slavery, but it’s interesting to float the analogy.

![[René-Jacques5.jpg]](http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_MmRVVROy-Jo/S4-lWM91ptI/AAAAAAAALFY/4imxrTW6wPI/s1600/Ren%C3%A9-Jacques5.jpg)