This emerging story of how the major banks have been misreported the interest rate they were paying to borrow/lend money to each other is beyond outrageous. The LIBOR (London InterBank Offer Rate) is has many uses and this fraud corrupted all those uses.

For example it signals what the market thinks about the stability of the banks, so by reporting the wrong values the banks were hiding their instability. There is no doubt that if they had reported it accurately then at least some people would have reacted. For individual investors those reactions could have saved them from huge loses. For regulators it might have reduced the magnitude of what happen in the world economy.

But that is not why the banks were engaged in this fraud.

It’s not often you get to talk about quadrillions of dollars; but this is a good time. The US economy in total produces around 15 trillion dollars a year. But there are financial instruments around which 500+ trillion dollars worth of trades happen a year. The LIBOR forms the foundation for some of these instruments. The banks undermined these markets by manipulating the LIBOR. It looks to me like quadrillions of dollars of transactions are now in doubt.

…

I’m reading “Red Plenty”. It is, sort of, a series of short stories about the Soviet Union’s experiment with central planning. Each story is a beautifully written; with sympathetic and complex characters. I was delighted to encounter in the midst of it a story about a middleman. Literature where the middleman is the hero are exceptionally rare, but apparently not entirely so.

One of many threads that runs thru the book is how the central planners are caught between a rock and hard place. For example at one point the eggheads point out that nobody can create a supply meat at the regulated price and convince the planners that if only they would raise the price of meat sufficiently then there would be meat. So, they raise the price, the workers complain, some of them step into the streets, some of them gather in the town squares. Some local officials say unfortunate things. Soon men appear on roof tops and bullets tear into the crowd.

A problem of central planning is that you lose the plausible deniability that markets provide. When the market raises the price of meat the public doesn’t march out of the office building and into the town square; and even if does the elite merely shrugs and mutters: “Tell it to the invisible hand.”

But in sense that’s not true. Political scientists assure me that the single most potent predictor in electoral upsets is the public’s sense of how much better or worse off they are v.s. 12-18 months ago. So the embrace of a market economy v.s. a centrally planned one doesn’t entirely shield the political elite from the being asked to take responsibility for hard choices. One group of the elite capture the benefits for disruption while others are take the blame for the resulting displacement.

…

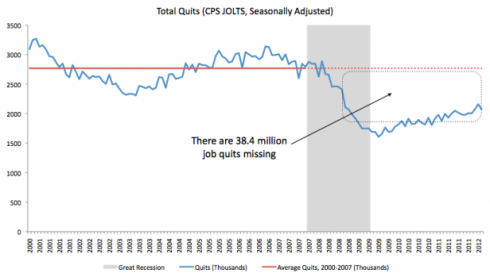

This chart from Mike Konczal illustrates a fascinating statistic that I didn’t realize the government collects – how many people quit their job. Mike posts this statistic because of a conversation that’s broken out in one corner of the blog-o-sphere about – a worth conversation about how if we are to go all gushy about “freedom” we really ought to spend some calories discussing “freedom” inside of commercial contexts. In particular how much or little freedom most employee’s have. Unsurprisingly there are people on the Internet who whole some pretty outrageous opinions. For example that there’s not problem with the boss insisting that you sleep with him, or wear diapers rather than use the bathroom; since your always free to quit.

Quiting is, is of course, one of the ways firms get clear feed back about their employment regime. If lots of your workers quite, presumably you might adjust your terms of employment. Hershman wrote a nice book about this “Exit, Voice, and Loyality;” where in he makes short work of the fanciful presumption that exit – the best loved feedback signal of simple economic models. Early in the book he allows as the claim that exit works as a feedback signal has no experimental data to back it up.

What this chart shows is that when the economy tanked people stopped quitting in droves. Apparently 38 Million corrective signals have gone missing. What can this mean? Three thoughts come to mind. Employees have become significantly more loyal or vocal. Employers have become much nicer.

Where are the statistics on the volume of employee voice?