bash-3.2$ curl -I http://www.sun.com/

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Server: Sun-Java-System-Web-Server/7.0

Date: Fri, 26 Feb 2010 15:39:03 GMT

P3p: policyref="http://www.sun.com/p3p/Sun_P3P_Policy.xml", CP="CAO DSP COR CUR ADMa DEVa TAIa PSAa PSDa CONi TELi OUR SAMi PUBi IND PHY ONL PUR COM NAV INT DEM CNT STA POL PRE GOV"

Location: http://www.oracle.com

Content-length: 0

bash-3.2$ Monthly Archives: February 2010

Amalgamation

I like how this quote shines a nice light thru the early 20th century literature on consolidation, amalgamation, aka trusts.

“Where combination is possible, competition is impossible.”

While unsurprising it’s frustrating how the left/right debating points have remained the same for over a century

Style as a Middleman

I’m reluctant to write this up. I feel I’m wandering onto really fresh turf here. Because this is really about style and design; and the various audiences that craft addresses. Something I don’t really know anything about.

One thing that caught my fancy in the book “Buying In” was the idea that products are two faced, like the middleman. Products you use in public, like an iPod, have one face they show to the public and another which they show to you. To hear him tell it when the iPod first appeared cultural observers took two quite polar positions about it. Some celebrated way it empowered a deeper intimate relationship between citizens and their music collections. While some railed about how the white headphones created a tribe, a kind of social signaling, and members of this tribe were walling themselves off inside a cult of iPod.

There is a large literature that presumes most style and fashion exists to serve a social signaling function. For example to denote membership in a tribe or to make the owner appear high-value. And no doubt that is one function of style, but yet I’m starting to think such talk is often just a cheap shot. It’s easy to see the signaling, the public face of the product. It’s hard to see the private face. Intimate relationship between the user and the product and intimate and complex relationship between the member and his tribe.

There are some products were this public/private tension is particularly high. I have a beautiful scarf. Nice enough that people feel free to comment on it. But they have no idea how sensual it’s cashmere is, nor other things about it I’ll pass over.

In another portion of the book he mentions how some publishers engage claques to ride public transportation reading new books, carefully so other passengers can take note of their dust jackets. In telling the iPod story it sounds as if Apple’s designers were largely unaware how the white headphones would create a unified field for the products branding. That white headphone decision appears to have been forced by the white packaging. Of course Apple is often quite aggressive in shaping the public face of their products. The iPod on the table here is black, but the headphones are still white.

The public/private face of stuff takes a odd turn when you move into a private space, say someone’s home or office. Corporate buyers sometimes decorate their offices with false signals to undermine the salesmen, i.e. photos suggesting hobbies the buyer doesn’t actually engage in. I once scanned the book shelf at a party only to become confused by the diversity of the owner’s taste. Later I discovered the owner was a publisher and he had a copy of most everything the firm had ever published.

I have gone into homes that are indistinguishable from a high end hotel suite. I wonder then, does this mean the owners have no intimate relationships with stuff; or does it mean they are just that aggressive about keeping that information private. I’ve been in the homes of some people so rich that they have rooms which reveal only a public self, while further in you’d find more revealing rooms. People do manage their public presentation of self, and if you often bring people into your private home then your likely to manage it there.

Yesterday Karim came at this from another side, writing on “The Anti-Social Nature of the Kindle.” He complains about how his Kindle denies him the ability to present a public face. But I notice how Amazon, the middleman, stripped one of the product’s two faces of as it passed thru their distribution channel. And while that must drive the publisher’s crazy, as Karim points out sometimes you want to reveal the public face of your stuff.

Into the Woods

A few people recommended this long talk by Van Jacobson, one of the many fathers of the Internet where in he argues for the need with a break with the past, something new in network architecture. What he is saying here has some overlap with stuff I’ve been interested in, i.e. push.

He argues that we have settled into usage patterns that are at odds with what TCP/IP was designed for. This is obvious, of course. TCP/IP was designed for long lived connects between peers; but what we use it for today is very short connections were one side says “yeah?” and the other side replies with, say, the front page of the New York Times. I.e. we use it to distribute content.

And so he argues for a new architecture. Something like a glorious p2p proxy server system. You might say “yeah?” unto your local area and then one or more agents in your local area would reply with, say, the front page of the New York Times.

The talk is a bit over an hour and fun to listen to. There is much to chew on, and like he says, it’s a hard talk to give. In a sense he’s trying to tempt his listeners into heading out into a wilderness. I’m not sure on the one hand he appreciates how much activity is already out there, in that wilderness. On the other hand switching to a system like this requires getting servers to sign a significant portion of their content to guard against untrusted intermediaries. There are reasons why that hasn’t happened. That he never mentions push bothers me. He points to a few systems that he finds interesting in this space, but I don’t think the ones he mentions are particularly interesting systems.

These are provocative ideas. Very analogous to the ideas found in the ping hub discussions and the peer to peer discussions. It would be fun to try and build a heuristic prefeching/pushing privacy respecting http proxy server swarm along these lines. No doubt somebody already has.

The Bimodal Nature of Work

One of the things that puzzles me about the vast literature on organizational dynamics, self control, will power, etc. etc. is that it seems to ignore an important reality about actual work. In my experience work comes in two flavors – everything is going just fine v.s. stuck. In the first mode you think you to know what your doing, the tools are reasonably helpful, and the problem at hand is receding as you work on it. That’s not to say the work is easy, it’s still work – unless your so lucky as to fallen into flow. But in the other mode one or more of these has decided to leave the building.

Users of complex tools are familiar with this bimodal problem. if you use any powerful desktop application (a Microsoft product, or an Adobe product for example) then you’ll have often experienced the second mode. We have all lost a day or two trying to figure out how to make page numbers work, the bibliography to appear correctly, etc. etc. These are examples where our skills and the tools conspire to push us into the second mode. The no progress mode is being made mode.

The more you push the edge of your skills or adopt new tools, or work on fresher problems the higher the chance your going to fall into this second mode. I suspect some trades spend large portions of their work lives in this second mode.

It is trivial for an outside observer to misdiagnosis the second mode and describe the situation as not working. He’s happy to point out that no progress is being made. Duh! And he’s happy to dust off all the usual suspects; e.g. moral failings of various kinds.

You can see occasional hints that this or that an organizational scheme addresses this by the appearance of terms like “management reserve,” “friction.” In Scrum the use the term velocity. But none of these dare to admit that work falls into the second mode. None of them speak to the puzzle of how to estimate the probability of entering the mode. None of provide any advise for picking apart what is happening in the mode, which is a precondition for getting out of it.

The skills for thriving in this mode might be called persistence. That’s really a distinct skill from skills that keep you on task in simpler times. At least I think so. The will power to maintain focus is somehow different than the willpower required to survive a long period this second mode where no measurable progress is being made. And while persistence is one strategic approach an alternate one could be named agility, aka change course. Again the moralistic outside observer might see that as quitting. The complementary pair of persistence and agility reminds me of Levy walks.

Nobody celebrates just simple businesses that work.

“Nobody celebrates just simple businesses that work.” – Matt Haughey

Nice. But. There are reasons for that. A bunch of the reasons are prosaic side effects of the conventions of story telling and the appetites of the audiences of reptilian brains. Setting those aside, but near neighbors, are reasons arise from our perverse fascination with creative destruction. And that has a tangle of threads, the most toxic of which is the confusion caused by a preference of robber barons to be called entrepreneurs. A trick made possible almost entirely by virtue of our presumption that a hero must appear in any story since all the stories we tell have heros.

But once you get past all, well. Simple businesses tend to be road kill waiting to happen. Simple businesses tend to lack a solid competitive advantage. For example a potent barrier to entry. They also tend to fail to accumulate sufficient body fat to survive a vicious downturn or the arrival of a game changer in their midst. When you step back, simple businesses are often just tragedies waiting to happen

MeFi is a delightful institution, a business that has worked for years. Or has it? It took six years to achieve lift off. So it’s been a functional business for maybe five. MeFi’s 10%/year growth is low for an durable internet business, but it’s not that exceptional. Just possibly what he means by simple is businesses with non-cancerous growth trajectories. Reading the interview where Matt says that you can see how other businesses have appeared around it. Many of these didn’t survive and some of these are much larger.

I have opinions, but certainly no predictions, about MeFi’s trajectory going forward. It would be tragic if it fails as a business, if only because of what Matt would suffer. MeFi is a member of a class, i.e. places where questions are answered. Yahoo has one. Google had one. The puzzle in these is how to leverage crowd sourcing on the one hand and control quality on the other. If MeFi succeeds in the long run it will because they found a course thru that space. Doing that isn’t simple.

All this resonates with the blurb from a paper (pdf) in my to read stack:

Good word of mouth requires a simple, compelling argument. Stock clubs and individuals select stocks from the same universe of choices, but members of clubs have to convince each other to buy a stock whereas individuals need only convince themselves. This paper shows that stock clubs tend to choose stocks that have a compelling rationale that is easy to communicate. Unfortunately, those compelling rationales don’t lead to better stock-picking performance.

I guess the good news is there is they don’t write “leads to worse performance.” But all this, brings us to a curious detail. That many businesses that are celebrated for their simple virtuous nature, well they usually aren’t that simple. It’s more likely the story teller didn’t know what to ask. Those stories are usually a fairy tale. They may be virtuous though, but that’s hard to say.

Singing in Unison

Conversation Hacking

This long essay on Trolls (or Conversation Hacking) is quite fun.

This long essay on Trolls (or Conversation Hacking) is quite fun.

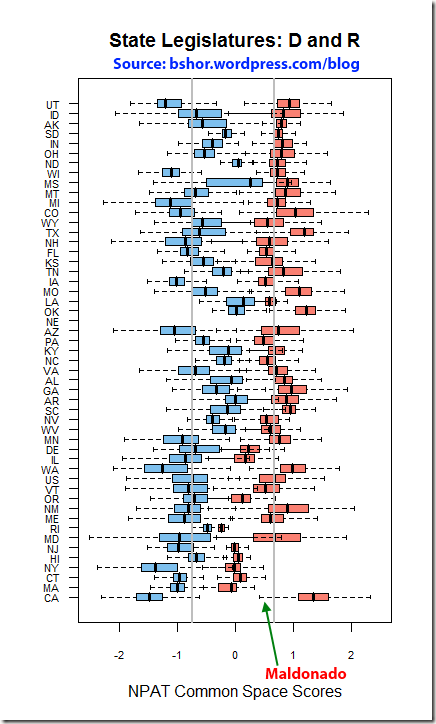

Polarization in the state legislatures.

Maybe I don’t read the right blogs but I’m delighted to see a blog post that actually looks at politics from the perspective of the common space scores. The chart below shows the distribution of the scores for various state legislatures (i’ve no idea what the order means):

This is a very instructive chart. CA, UT, WI, FL, and WA have no common ground between the parties. I’m surprised they let NJ, HI, NY, RI, and MA Republicans into the hall when national Republicans gather.

California is an object lesson in where we are headed if the nation doesn’t figure out how to back off from the polarization between the two parties. I wonder, does a requirement for a super majority tends to help consensus when there is a large overlap and tends to create an incentive to polarize when the overlap weakens?

(HT: Gelman)

Match Making Machine

Match making is at the heart of most middleman functions. The buyer and seller work thru the middleman to improve the chance of closing a transactions. Both sides reveal information to the match maker who then puzzles out if a deal can be closed.

The negotiation literature is full of examples where the negotiations fail, in spite of the existence of a deal to be had, because the two parties reveal information along a path that leads to a lousy outcome. The simplest example is negotiating over price. The rule of thumb is that once each side has bid a price the only possible outcome, short of a great deal of negotiation, is to split the difference. The rub here is that each party has a space of acceptable deals and the challenge of the negotiation is to both discover if they overlap and then give that find a good point to close on. But the moment one side reveals anything about his space of acceptable outcomes the other side will adjust what he reveals.

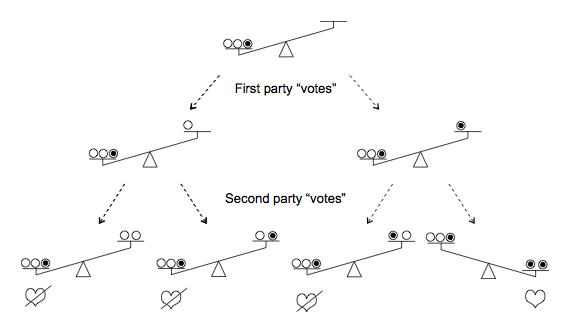

The following illustration is taken from a paper that suggests a way, using cryptography, that two parties might check if they have found common ground without actually revealing anything about the ground that is acceptable to them. The paper frames the match making as a romantic problem (Romantic Cryptography (pdf) in the Journal of Craptology). The two sides want to know if they love each other without revealing their love.

The balance beam below tries to solve this problem. The players place tokens on the right side. These tokens are identical to the eye, but are either light or heavy. In the drawing the heavy tokens have a dot shown in their center. A player who loves the other player places a heavy token on the scale. Once both players have placed their tokens a pin is removed and if the scale falls they both love each other.

You could use this in price negotiations. You using a spinner to suggest a price and then both sides play a round; repeating until a mutually acceptable price is discovered. It could also be used to make all kinds of self revealing games; say with a deck of cards that ask questions.

Of course in this story the device, the scale, is acting as the middleman. The paper sketches out how to do this kind of thing with cryptography.

I wonder if there is a simple way to cobble together a scale and tokens like this out of stuff likely to be lying about. The need does arise. Say for example when a team wants to know if they all think it’s time to cancel the project, delay the release, switch database engines, fire the project manager, hire this guy, …

The paper goes on to describe variation on the technique using transparencies.

Each player is provided with two transparencies, a yes and no vote, that look similar the ones above. If the two yes votes are overlaid you get a heart. Otherwise you get nothing. The first approach requires some carefully made tokens and scale that works just os. This technique requires preparing the transparencies for each round; but they can be manufactured before hand into a deck for use during the negotiation. It’s fun to note that a similar technique can be used so the players can distinguish if which of their cards are yes or no.

They point out that there is a problem with lying. If the game reveals both sides love each other it’s still a problem that they might say “Oh, just kidding!” Placing a bond or playing the game in a group can help to put a price on that behavior. There is somewhat different problem that raising a question reveals a lot, as in the example “Do you think we should fire Bob?” Some of that can be addressed by creating a swarm of random but oft raised questions.