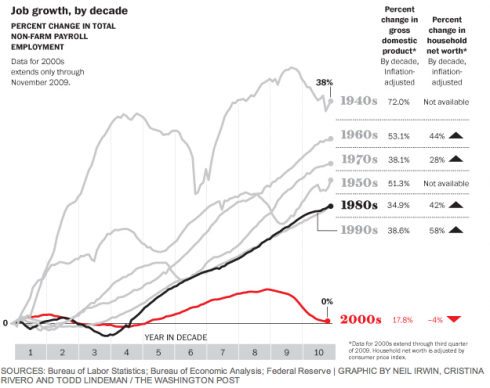

Oh man that is ugly, and as the column on the right shows household net worth is even worse.

Category Archives: politics

Enabling Change

I was working with someone a while back who was in the midst of advocating for an alternative approach inside his organization. He was frustrated. He was deeply convinced of the benefits of his new approach and frustrated by his colleagues passivity. My first thought was to recall a few of my lists, for example this one.

But later I got to thinking – I do have the list he was looking for.

- enable small wins

- provide field trips where the problem can be observed in the wild

- increase contact with actual users, preferable ones with high emotional trigger; i.e. fame, sympathetic, impedence matched, etc.

- don’t ever attack or dismiss their core competency, e.g. do not propose your new approach in contrast to existing practice

- invite them to join you solving your sales problem, e.g. create an imaginary client and discuss your challenges selling to that client

- lots of short stories of others using the approach helps – it creates social proof, demonstrates value, invites a monkey see monkey do pattern

- create clear low cost affordances for action

- stand ready to encourage anybody who exercises those options

- plan out how this blends into existing their time management

- plan out how this blends into existing sources of encouragement

- plan to provide air cover, money, staff, and to resort their objectives

- map out existing social networks and know that it’s the network not the individuals you need to transition

You can use that list to for an initiative (both to help or hinder), and you can use it to shift culture. Two take two examples of culture – if your organizations tends to pile on lots of objectives or very a narrow repertoire for giving encouragement you can be sure that new ideas are being squeezed out and adaptability suffers. Of course adaptability it not an unalloyed good.

Density, Hierarchy, and Power

This is a post about why gerrymandering might not be as unethical as it appears; or maybe it’s about the hidden agenda of those who argue against it.

Each time you encounter a highly skewed (power-law) distribution the population spread out on the long tail can be assumed to suffer from a severe coordination problem. Being numerous, banding together to advocate for their common interests is harder. Meanwhile the population at the elite end of the distribution have a much an easier time coordinating their actions. By an example consider overdraft fees – it’s a lot easier for banks to get it together for their prefered regulation than it is for bank customers.

The natural disadvantage of the diffuse and numerous doesn’t prevent the elite from worrying about the little guy ganging up on them. This is old news. In Dicken’s Hard Times we get this dialog.

” All is shut up, Bitzer ?” said Mrs. Sparsit.

“All is shut up, ma’am.”

” And what,” said Mrs. Sparsit, pouring out her tea, ” is the news of the day ? Anything ?”

” Well, ma’am, I can’t say that I have heard anything particular. Our people are a bad lot, ma’am; but that is no news, unfortunately.”

“What are the restless wretches doing now?” asked Mrs. Sparsit.

“Merely going on in the old way, ma’am. Uniting, and leaguing, and engaging to stand by one another.”

“It is much to be regretted,” said Mrs. Sparsit, making her nose more Roman and her eyebrows more Coriolanian in the strength of her severity, ” that the united masters allow of any such class combinations.”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Bitzer.

” Being united themselves, they ought one and all to set their faces against employing any man who is united with any other man,” said Mrs. Sparsit.

” They have done that, ma’am,” returned Bitzer; “but it rather fell through, ma’am.”

In spite of that we encourage this uniting in numerous cases. The California Raisin Marketing Board for example brings together small producers. We often write regulations to encourage or force the pooling of common interests like that. From trade association to the interlibrary loan system there are plenty of examples.

Often these schemes involve a certain amount of coercion. Clearly an urban voter could be a little peeved to discover a Montana vote is twice as potent as his and no doubt there are some California raisin producers who would rather go it alone.

So the menu of schemes for enabling, encouraging, or forcing solidarity on the members of the long tail interest me. These are the tools for community forming, and one of the most venerable is representative government. You can’t run any large organization with direct democracy; sooner or latter it’s a good idea to encourage a bit of intermediation. At some point the town meeting doesn’t work. So you start electing representatives instead.

Ok, so here’s the point of this post.

Andrew Gelman draws our attention to an political science article (pdf) that throws new light on ethical puzzle of how to draw congressional districts. The whinging crowd loves to make fun of how bizarrely shaped congressional districts are. Oh the horror, they cry, look politics has tainted this process. I’m not sure what they expected, but yeah.

Let’s say your state has two kinds of people, good people and bad people, and they are split evenly 50/50. Your a good person and lucky you you’ve been given the power to draw your three congressional districts. So, obviously you draw them so that 80% of the bad people are in one district; thus come election time you’ll get two good congressmen and you can limit the damage the bad voters can do to one congressman. Such cartographic manipulation is obviously fraught with ethical implications. Not the least of which is how it leads to increasing polarization, reduced competition and absence of discourse.

You might be able to achieve the above goal indirectly. For example if all the good voters live in the country and all the bad voters live in the cities then you could lobby for rules that requires congressional districts to have small perimeters, i.e. to be compact. That would tend to trigger districts bundle up those bad urban voters in compact little districts. As a fall back position you can’t get of rules adopted that arguing for compact districts you need only argue for such districts on cosmetic grounds.

The article asks: Does a political party who’s voters live in dense regions have some significant structural advantage or disadvantage? Their answer: yes, a big one. If representatives are drawn from geographic regions and there is a preference for compactly shaped regions then a party that draws principally from rural areas will have a substantial advantage. They focus on Florida and use detailed data for the two parties to show that a preference for compact districts gives the Republicans a significant structural advantage given the concentration of Democratic voters in urban districts.

One last thing, communities of common interest aren’t always aligned with geography. While the raisin growers of California probably have some geographic coherence other groups, e.g. doctors or school teachers, don’t. For the last century or two communities have been becoming increasingly a-geographic. It is a fun sort of sci-fi like fantasy to imagine representative district lines that are dawn in virtual rather than physical space. Then the senator from the Auto Industry wouldn’t have to live in Michigan.

The Perverse and Invisible Hand

I have recently started reading Albert Hirschman’s 1991 book “The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy.” I’m only 20 pages into it so no telling where it’s going. But so far, it has totally blown me away. The book is an outline of three styles of rhetoric that are commonly used by reactionaries, i.e. those who would react against progress. These are generic arguments good in most any situation. Introducing free speech, extending the franchise, ramping up public education, rearranging the kitchen? You name it these rhetorical devices stand ready and willing.

He labels the first of these “perversity.” Here in while reactionary pretends supports the goal he then goes on to explain that efforts toward that end are certain to backfire. Efforts to improve health care? Such efforts will decrease health care! Universal schooling? Such efforts will lead to wide spread idiocy. Do-gooders make things worse. The audacity of this argument is breath taking. But look at the record! How that French Revolution turn out?

Hirschman points out that observers of the French Revolution quickly deployed this argument. Even before the it all went to hell in a hand basket. Edmund Burke in particular used this perverse argument, and later when it things got ugly he got a lot of credit for being so insightful. So did Burke invent this technique? Hirschman argues that no, Burke was mimicking newly popular argument with a similar structure that had recently arisen in the circles he ran in. I.e. the hypothesis of Adam Smith. Aka, the Invisible Hand. This takes my breath away!

The invisible hand is a perverse argument. But in this case bad actions (individual greed, personal vices, and self interest) have the unintended consequence of creating a vibrant national economy. It’s as if God in his infinite wisdom had sus’d out how to turn his flock of sinners into something constructive. Smith might have given credit to divine providence but choose to give the credit to more amorphous but still spirtual invisible hand. Many of Smith’s readers saw right thru that. Particularly all those commercial actors looking to get the church off their case.

I can’t seem to stop chewing on this. It goes in all kinds of directions.

There are numerous systems where actions sum up to something surprising. I can’t believe that I hadn’t noticed how Evolution and the Invisible Hand are both theories of a kind. In evolution the bad (dyslexic genes, mutations, death, mindless long time) that shapes inconceivably marvelous species. There is, it appears an entire class of theories where acts of ethical kind sum to results of the opposite kind. God works in mysterious ways.

I am enjoying this book.

Joking == Industrial Revolution

Asked what the earliest known joke is Robert Mankoff, here in this long geeky video on cartoon humor, spins a tail saying: Shortly after the Civil War. He tells a two awful early proto-jokes, one from the Greeks along with another from the century before the Civil War. He’s wrong about this as you can see from this article from last May reporting the discovery of a Roman joke book.

We are talking here about jokes, not humor. Obviously Pride and Prejudice and much of Shakespeare is hilarious, but the jokes are nonexistent. Let’s give a joke by example to help clarify, lifted from the that article on the Roman joke book:

a barber, a bald man and an absent-minded professor taking a journey together. They have to camp overnight, so decide to take turns watching the luggage. When it’s the barber’s turn, he gets bored, so amuses himself by shaving the head of the professor. When the professor is woken up for his shift, he feels his head, and says “How stupid is that barber? He’s woken up the bald man instead of me.”

A joke is very brief, even one line; and it’s not really the same as a quip, like say the amusing rye observations that Jane’s father makes in Pride and Prejudice. A joke is a little stand along machine designed to trap it’s audience into laughing.

But obviously Mankoff’s version must have some grain of truth in it, since watching the video it’s clear that he has deep familiarity with the history and theory of humor. I can accept that the discovery of an ancient joke book is in fact an extremely exceptional event. Which I find entirely bizzare. If asked to guess I’d have presumed that joke books would be close on the heels of pornography as one of the first things an entrepreneurial book printer would print up for his customers. And, I gather, that many great Universities have significant collections of dusty books of porn; so why no similar collections of jokes?

That says something, I’m just not sure what. Joking seems to fundamentally human that I can’t help but presume that some serious social controls censored the behavior so it was extremely exceptional for the behavior to get up enough steam that joke books survived. Maybe something about the state of the art in joking, which is largely consistent with Mankoff’s model. Maybe something about the nature of self censorship, e.g. maybe joking was treated as more sinful than pornography and or the demand for porn displaces the limited time for making possibly sinful books for resale. Maybe it says something about archivists. Maybe all these and others?

All this reminds me of another example of human activity unknown until modern times, i.e. political demonstrations. For which similar questions could presumably be asked. I joke that it’s my right as an American to complain, and apparently it is in fact a very modern right. Maybe the right to joke is similarly modern. There are days when I think modern human culture really is entirely different from what passed prior to say 1750.

Are all these modern activities fundamentally out of scope, i.e. sufficiently suspect as to be worth vigorous suppression, for a true conservative?

Community Stress Metrics

When dealing with communities it’s nice to have some frame works. For example I like both the one from Collaborative Circles and this one. And I often highlight how the common cause that binds a community can be outward facing (defensive) or inward facing (building something). Here is another one: a dozen metrics for sensing when a nation is going to hell in a hand basket. The combination of a community of that scale with a failure of that magnitude means the list is full of exaggerated speech. But clearly it’s useful for smaller communities, for lesser stressors. It’s kind of amusing in fact to apply for more trivial things: The death of the goldfish created the demographic pressure that lead to Debbie considering running away from home.

- Social

- Demographic Pressure

- Displacement

- Group Grievance/Paranoia

- Flight

- Economic

- Changing Inequality

- Decline

- Politics

- Club losing it’s legitimacy

- Deterioration of club services

- Arbitrary rules and abuse of member rights

- Failed oversight/auditing of those who enforce the rules

- Polarization of Elite members

- Loss of the club autonomy, intervention by outsiders.

All these pressures ebb and flow in communities. You get demographic pressure when every you hire or fire employees, or when the students come and go. Bureaucracies often fall back on arbitrary or abusive enforcement. Oversight is always spotty. The elites are rarely always on the same page. These are always a matter of degree.

When the going get’s rough these all get tangled, so a list helps to tease them apart. But they certainly reinforce each other.

For example. Harvard, about whom I have zero personal knowledge, has suffered a substantial decline in it’s economics. I gather there has been a decline in the services (no hot breakfasts) the university provides to it’s students. Is talent in flight? I’ve no idea if any of the other metrics have taken a hit.

Actors seeking to increase the level of discontent, i.e. violence entrepreneurs, can talk up all these to create an impression of pending failure. For example talk up fear of foreign influences, immigrants, police abuse, battling elites, reduction of public services. Sounds like the insurance industries and it’s right-wing agent’s battle against healthcare, eh?

The Races

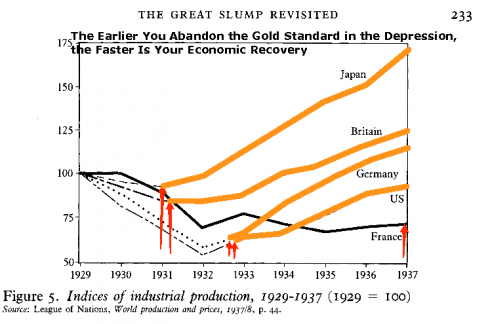

This first chart shows the economic growth of various nations during the years of the Great Depression. The red arrows show when each nation abandoned thier commitment to extremely ‘sound money’ as represented by the gold standard. (The original source pdf.)

This second chart is about the current recession. It shows the correlation between the level of fiscal stimulus and GDP growth in various countries. Aggressive stimulus leads to a faster recovery.

I have wondered how much that first chart is all you need to know about why we ended up at war with the Japanese. Word for the day: calutron.

Close monitoring, profiling, and sin taxes

Cars get into accidents. Adding cars to the system increases the number of accidents. The paper discussed here argues that adding a car in a high traffic state adds about $2,500 worth of additional costs, almost $7 dollars a day! Here in Boston, a bus/subway transit pass costs a bit less than $2/day. My somewhat dated estimate of the cost of car ownership was $13/day, of which $1.25 was insurance. Of course that $7 is at the margin and the insurance isn’t.

The authors suggest using Pigouvian taxes as a way to reveal the true costs of their $7/day externality. Sin tax is the common name for Pigovian taxes, i.e. taxes that are designed to bring market forces to bear on behaviors that are high cost in the big picture but appear to be costless as they are being engaged in. The authors suggest a gas tax or a change in how insurance is priced. Per-mile charging would be preferable to per-year charging.

There is a trick some groups use to get people to show up on time. They set out a jar and if you show up late for the meeting your required to quietly deposit a dollar in the jar. That’s a Pigouvian tax. Otherwise the guy showing up late is inflicting a coordination cost on everybody in the room. He’s getting a free lunch. Later you can buy everybody a free lunch with the content of the jar. This can backfire :).

Tax design is a fascinating puzzle. Lots of dimensions! One dimension that is often ignored is how easy it is to avoid the tax. Back when I lived in NYC it was common to observe cars who’s license plates signaled that my neighbors had registered the car at their summer place in Vermont. Here in Massachusetts it’s common to slip over the border into New Hampshire to buy larger items sales tax free. A friend of ours reports that the current tight credit situation has move more of her income into the cash economy.

In practice it is easier to tax immovable things, like real estate. Pigouvian taxes are hard to implement because behaviors are hard to tax compared to capital assents. To first order it’s behaviors that cause externalities. A consumable (beer, cigarettes, gas) can help with that. Profiling can help, i.e. if we know John runs red lights, a smokes, a he’s a heavy drinker…

Just as we are doing more behavioral advertising, as technology lowers the cost of close monitoring and erodes our privacy we can do more of behavioral taxation. Charge those guys that grab a free lunch by darting thru the intersection after the light’s changed. The public will have mixed opinions about all this, but framed right they are likely to like the idea of taxing behaviors that have high externalities. The congestion pricing schemes for cities are an example of this. Are we at a tipping point for this stuff?

I’m surprised that the current crisis hasn’t triggered any (?) moves in this direction. How hard is it? For example, most states have managed to get most of their drivers to adopt their drive-by toll collection systems. They could make that manditory and institute a mess-o-tolls. I’m confident it wouldn’t be hard to repurpose that system to catch red light scoff laws.

Or states could use their drivers licenses to raise taxes on people who have a problem with alcohol. They could even do that entirely on an entirely volunteer basis, following the model that Arizona uses where people can sign up to be barred from entering casinos.

I’m amazed that not a single state has raised their gas taxes. Many states have raised their sales tax. Treating undifferentiated consumption as a greater sin than driving seems bizarre to me. Sales taxes are also a very regressive tax.

I don’t know how this will work, but you can play the design your own Pigouvian tax game here. That uses moderate.google.com, which lets you post issues, collection ideas, etc. I’ve posted some things that have short term pleasures for those who do them, but longer term costs for the rest of us. Feel free to add others and possible Pigouvian taxes to compensate.

Separated

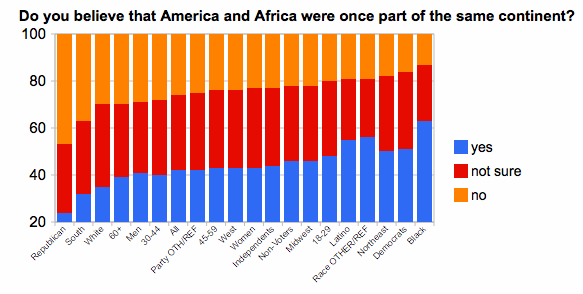

The folks at DailyKos have an interesting series of surveys. The second question from this one has been getting a lot of play recently, but the first question is interesting as well. A lot of people no longer identify as Republican and those left behind are settling into increasingly minority opinions.

Thanks to Jim I’ve updated the chart so the two uses of OTH/REF (presumably Other/Refused) are distinguished.

Now to a second question, how come I’ve never seen stacked bar charting software that let’s be adjust set the bar chart width based on yet another number, i.e. how part a share of the sample was in that vertical?

Voteview: Supreme Court

That is the voteview plot for the current supreme court; which can be contrasted to the same plot for voters in various states. The horizontal axis accounts the vast most of voting behavior and is a measure of economic liberal-conservative; i.e. the degree that government should shape markets to the benefit of small v.s. large economic entities. You can see the distributions for the last congress here, along with where the president fits. The vertical axis is social issues; higher is more socially conservative.

Update: More here.