I take the bus to work most every day and recently I’ve noticed two new, to me, syndromes. First off I’ve noticed that I catch later of two morning buses it will passes the earlier bus on it’s way. Secondly I’ve noticed that if the bus is even a few seconds ahead of schedule this advantage will accumulate so that it arives at the train station quite a bit ahead of schedule. Both of these have to do with passenger loading delays.

The 2nd bus wins because it is less popular, so it stops less often; while the 1st bus is very popular and has to stop a lot. It’s the passengers, and their loading time.

The second syndrome, where the amount a bus is running ahead of schedule piles up is also due to the passengers. In this case the bus doesn’t have to pickup passengers who come out to the bus stop on schedule. I’ve noticed that when I miss my favorite bus, but I’m on schedule, it will drive by empty – which of of course get’s my goat.

These are interesting complementary syndromes and they suggest that being on schedule is unstable. Early buses tend to become even earlier, since the load they usually carry doesn’t appear; while buses that run late tend to accumulate additional loading costs. It’s fun to think about how one might overlay some regulatory scheme to temper these effects.

Seems to me there is an analagous syndrome in projects. Delayed projects tend to accumulate more items, as the delays allow more requirements to show up and pile-on. Projects ahead of schedule tend to pick up speed as they drive pass additional requirements which haven’t managed to get the meetings on time.

It’s interesting to muse about what interventions one might take in these situations. Driving by a few bus stops to get back on schedule, or explicitly ignoring a few project requriments is very hard to execute on. There is one bus driver on my route who appears to have discovered that he can spend a lot more time drinking coffee if he gets ahead of schedule; the man’s a maniac. I’ve worked with managers like that.

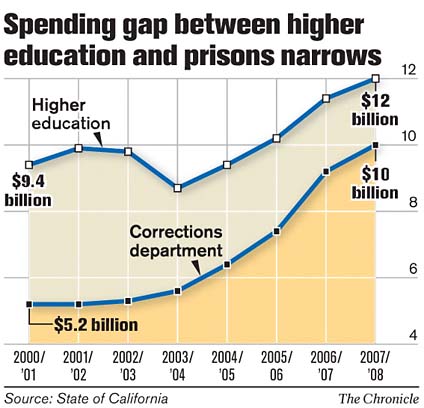

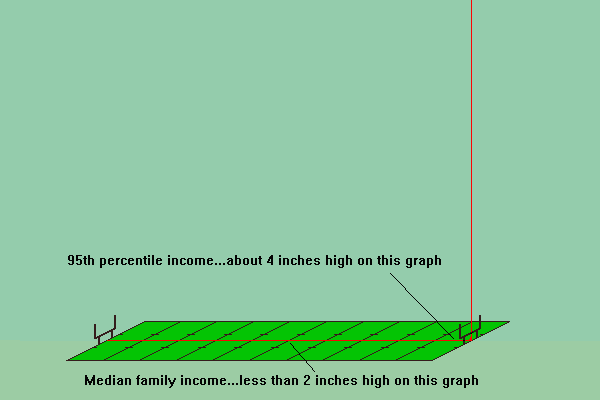

Both of these do a nice job of helping to visualize the actual shape of these curves. They help to clarify why the politics and business models that serve the two legs are very different and why the appeals that emphasis middle class values are should be treated with some suspicion. The more typical illustration, shown to the right, is preferable if you want to deemphasis the polarization and highlight the uniformity of the underlying generative processes.

Both of these do a nice job of helping to visualize the actual shape of these curves. They help to clarify why the politics and business models that serve the two legs are very different and why the appeals that emphasis middle class values are should be treated with some suspicion. The more typical illustration, shown to the right, is preferable if you want to deemphasis the polarization and highlight the uniformity of the underlying generative processes.