I’ve thought and read about cities for decades so it is extremely cool to encounter a new idea. I’m currently on vacation in Ithaca NY, and before hand I wandered into the Architecture library at work to pick up a book about the Finger Lakes region. That book was a disappointment, but nearby was a big thick book confidently called City about New Haven Connecticut and as is my wont I picked it up too. City: Urbanism and Its End by Douglas Rae adds two new, to me, pieces to the puzzle of what happened to the American cities.

My father used to tell a story about a scholarly study of what climate is most suited to civilization. The scholars plotted latitude of the great civilizations down through the ages. Fitting a curve to their data they showed conclusively that the current optimal location of a civilization was New Haven Connecticut. Needless to say the scholars were at Yale. I grabbed the book in the hope it would turn out my father’s story wasn’t entirely tongue and cheek.

Geography does shape civilizations of course. The presumption that Yankee thrift and innovation is a consequence of the Puritan culture, to take a common example, is thrown into question by the story of how the Puritans who migrated to Central America at the same time ended up being slave owning oligarchs. In that case the distinguishing factor appears to be labor availability. In New England labor was dear, land wasn’t; while in the Central America it was the other way around. Dear and innovation go hand and hand.

The thesis of “City: Urbanism and Its End,” beautifully and delicately presented in the first chapter, states that cities, like New Haven, made sense as a coordinating device only for a short period, less than a century. It’s conventional to say that the automobile killed the center cities and in models of that kind the primary driver of how concentrated our settlements are is the transportation system used to glue them together. Old cities in Italy have narrow streets because they were used on foot while modern urban spaces care more about tractor-trailers than tricycles.

The usual complement to the transportation based models of city concentration are ones about endowment. First there were the natural endowments, a good and defensible harbor or along an existing trade route for example early London or New York’s are examples of that. Later cities became their own endowment; aggregating social networks, capital, functional governance, etc. etc. San Jose, and Silicon Value, is a modern example and Venice or Amsterdam a older one. This model of cities as aggregating increasing returns in their endowments is my preferred model for what shapes the concentration of populations into cities; in part because it seems to fit well the power-law distribution of city sizes.

In the years prior to the rise of cities like New Haven the population was concentrating into what he calls Fall Line Cities, i.e. cities build along a river that was rapidly descending so as to take advantage of water power. Labor, capital, expertise, the whole complex knot needed to make industrialism work, had to migrated to the power source. That changed with the advent of steam power, railroads, coal, etc.

So that’s new to me. Energy was no longer dear, or at least no longer immovable,it could no longer command all the other elements of the party to show up where ever it happened to be. Once energy stopped being the key endowment other factors became the hard thing coordinate. The city became the party. One consequence of that insight is to wake up to the key role that electricity plays in blowing apart the 20th century central city. It is, possibly, just a critical to the story as the automobile. Before electricity you wanted to be near a rail or flat water to get your coal, to run your steam engines. This reminded me of another of my father’s stories. He had a friend who started a company making fiber optics, and that factory was carefully sited to be adjacent to a high tension power line near a small New England town with a concentration of optics expertise.

But there is yet another part to the story that is new to me. Some years ago I was shocked to watch how real estate interests in Massachusetts were able to override the governance of the states principle cities using a statewide proposition. Rae highlights how cities are seriously handicapped in the US by how their governance is structured. In 1907 the Supreme Court wrote: “The State .. at its pleasure may modify or withdraw all [city] powers, may take without compensation [city] property, hold it itself, or vest it in other agencies, expand or contract the territorial area, unit the whole or a part of it with another municipality, repeal the charter and destroy the corporation. All this maybe done, conditionally or unconditionally, with or without the consent o the citizens, or even against their protest. In all these respects the State is supreme.”

That’s why, for example, suburban and rural voters could pass a referendum over the objections of city dwellers in Massachusetts. That’s why New York city can’t get it’s hands on a half a Billion dollars from the feds for congestion pricing without sharing a large portion of the money with the rest of New York state. Why New York is attacked by terrorists and we send money not to cities but to states where it buys toys for rural police departments rather than improved harbor security. It’s why when the automobile began to undermine the numerous endowments that cities has accumulated they had such a hard time fighting back; and it goes a long way toward explaining why European cities were more successful in tempering the displacement of those endowments.

Of all the endowments cities have the diversity and richness their social and knowledge networks are the ones I find most fascinating. My father’s friend needed electricity and a pool of optics expertise he could draw upon. I’ve thought that eBay and Google couldn’t have happened in any other situation; they desperately needed the pool of expertise that only the bay area could provide. These endowments are the ones that Jane Jacob’s emphasises in her works. By the time she was writing cities were created innovation but as firms grew they threw their factories out into the periphery. Just as Apple manufactures in Taiwan, or Google puts it’s servers next to hydroelectric plants. It is, just possible, that the Internet will displace these social/knowledge endowment as well. While I don’t know how that will play out for cities what I do know is that it’s harder than it looks replicating those in on the fabric provided by the net.

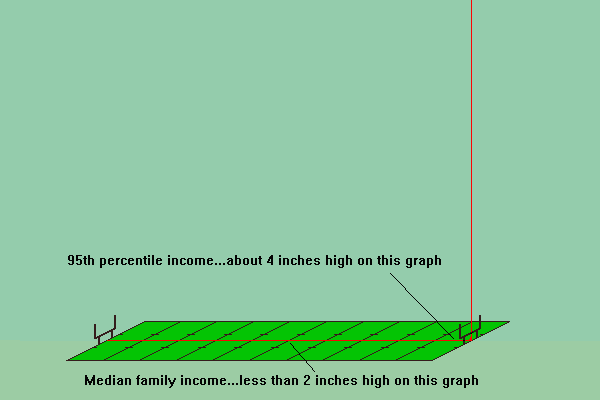

Both of these do a nice job of helping to visualize the actual shape of these curves. They help to clarify why the politics and business models that serve the two legs are very different and why the appeals that emphasis middle class values are should be treated with some suspicion. The more typical illustration, shown to the right, is preferable if you want to deemphasis the polarization and highlight the uniformity of the underlying generative processes.

Both of these do a nice job of helping to visualize the actual shape of these curves. They help to clarify why the politics and business models that serve the two legs are very different and why the appeals that emphasis middle class values are should be treated with some suspicion. The more typical illustration, shown to the right, is preferable if you want to deemphasis the polarization and highlight the uniformity of the underlying generative processes.