Kim Cameron’s Laws of identity reminded me to two things. First it reminded by of the This American Life episode on superpowers. One of the segments in that episode involves asking people which superpower they would pick: invisibility or flying. That implodes into a discussion of what the choice tells you about the person. My frivolous brain then meandered into thinking what superpower would I pick if I wanted to solve the identity problem; since Kim took “maker of laws”; I think I might pick “shaper of markets.”

The reason the Passport stumbled was that Microsoft hadn’t admitted that the shape of market power in their industry had changed. Prior to the Passport experience nobody in their “ecology” had aggregated enough market share (and in this case we are speaking of share of the identity market) to both care and decline to their leadership. Prior to that time frame Microsoft, on their bad days, could keep the puppies living in their ecology “chasing tail lights”.

Three things, at least, changed in the shape of their market. First the scope of the market blew wide open. For example, the Internet market included all the telephone companies. In the ecology metaphore Microsoft wasn’t king the forest anymore. Second the internet had already created a huge bloom of new players. Some of those were already really large; e.g. Yahoo, AOL, Amazon, eBay, etc. etc. Of those only eBay chose to follow Microsoft’s leadership. The third: Identity is critical to the business models of some of the players.

Notice we don’t even need to mention that the anti-trust case had revealed publiclly that Microsoft was capable of being a vicious monopolist when it’s market position was threatened.

Kim recently said that Passport failed because it broke one of his design constraints, i.e. that identity architecture will be more stable it’s designed to assure that the fewest parties are involved. Sure, that’s a great design constraint, but not because it’s makes the standard more stable in the long run. Aboslutely not. In fact it’s probably much less stable in the long run. Consider eBay; eBay is a very very stable business architecture; because it inserts a nominally unnecessary party – a middleman – into every single transaction.

Kim recently said that Passport failed because it broke one of his design constraints, i.e. that identity architecture will be more stable it’s designed to assure that the fewest parties are involved. Sure, that’s a great design constraint, but not because it’s makes the standard more stable in the long run. Aboslutely not. In fact it’s probably much less stable in the long run. Consider eBay; eBay is a very very stable business architecture; because it inserts a nominally unnecessary party – a middleman – into every single transaction.

That constraint is desirable because it makes your offering less threatening. It accelerates adoption, it isn’t a long term stabilizing force it’s a short term driver of growth. The kind of thing firms often, intentionally or not, use to stage a bait and switch. Meanwhile, have you noticed that the email announcing you

have made a purchse at eBay now includes a link that hands you off to Paypal thru DoubleClick! Have I mentioned that DoubleClick is the real leader in identity systems? Talk about unnecessary third parties!

To say Passport failed because it broke that constraint is all well and good but it’s a diversion. It would be a hell of a lot more straight forward to say that Passport failed because it fundamentally threatened the customers’ businesses and Microsoft lacked the market power to get away with that.

Ok, enough on the shape of markets.

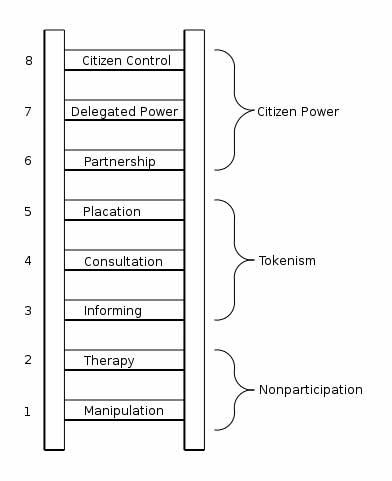

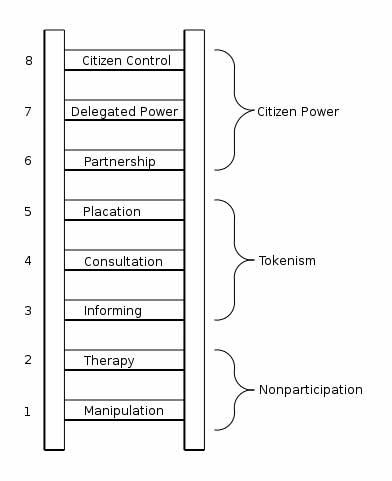

The second thing the use of the word “laws” reminded me of was the drawing on the right (from here).

What level on that ladder is the identity problem going to get solved

at? Where is Microsoft playing?

We get a hint from the use of the term “laws” rather than say “first draft design constraints.” When the software industry was defined by the desktop Microsoft could thrive as a business on the lowest rungs of that ladder. It would Consult – but at arms length thru market research or ad-hoc conversations at developer conferences. Placation was a job for PR. Partnership was an occasional activity to be engaged in with Intel, IBM, possibly Apple or Sony. The bottom three rungs where the job, for example, of the developer network.

Mostly they just used Manipulation. “Chasing tail lights.” “Cutting

off air supply.”

Marc Canter wrote recently that solving the Identity problem is 98% political. Absolutely. But, damn it, for the vast majority of the leaders in this industry politics means Nixon, Vietnam and not the New Deal and the Second World War. Many of them model the industry as small startups that ripped power from big firms and handed it over to small players. All that enabled by the PC and Moore’s law.

These folks the word politics is right up there with necrophilia on the list of ethical activities. It’s not an attitude that make it easy to work constructively on the top rungs of that ladder. Notice, the guy that drew that ladder couldn’t bring himself to label the top rungs “politics.”

The bag of of governance models for working on political problems is huge. For example, the standards process around Atom is a very modern one. I do not believe that Microsoft knows how to work at these levels constructively; 25 years of habit aren’t easily changed. I do not see any sign they have made significant progress in learning how since the Hailstorm debacle. I don’t think they even know what kind of debacle Hailstorm was. Look at how hard they fought to keep Sun out of WS. They only let Sun is as part of buying them out.

If you want to think seriously about working at that higher levels on that chart there are two groups trying to do that. WS and Liberty. (Disclaimer: I was involved in Liberty, but then I’ve also taken money from other players in this market.) It appears to me that only Liberty is actually trying to work on the political problem of solving the identity puzzle. Much higher on that ladder than any other group, by far. Not high enough; but much higher.

The spidering robots hired a

The spidering robots hired a  Martin Geddes in a

Martin Geddes in a  Kim recently said that Passport failed because it broke

Kim recently said that Passport failed because it broke