I’m interested in how groups form. It’s frustrating, most of the literature about groups is fixated on how they rot or how the gears in mature ones mesh. For example you can read floors of books on revolution. There is very little on what happens after the revolution. There is also a lot of thinly veiled liturature targeted at the frustration of people attempting to change some existing group.

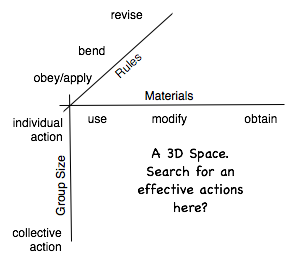

One thing groups do as they mature is they being to lay in various rules, procedures, practices, rituals, etc. to compensate for and temper assorted problems that have emerged as the group matured. Clay Shirky and Dave Weinberg both gave very nice talks about how groups emerge and and undergo constitutional crisis.

A friend asked the other day. Constitutional crisis? Body or law? A bit of both, I guess. The first constitutional crisis of a group is clearly of the body, a fever. If they go thru the fever, as versus backing off from it, then governance begins to emerge. From then on the body’s fevers and the rule rework engage in a kind of systolic ebb and flow.

To take a simple example consider the community around a Wiki. They initially allow any and all to drop in and add/maintain content. Inevitably something unfortunate happens. They then might institute some coordination device that helps to assure all changes get proofread by at least somebody within a week of going into the shared document.

This is the moment in the life of a group when the individuals in the group agree to relinquish some authority to the collective group. That’s possible only because the individuals have come to value the goods group is managing to create. (Well possibly some overarching authority might command that relinquishing, but let’s ignore that.) This adds a little refinement to the life cycle of the common cause around which a group rondevous.

Kieran Healy has a nice posting about professionalism. It includes this quote: “Professionalism is about relinquishing something.” That’s not limited to professionalism; that’s part of the price of membership in mature groups.

Which brings me to a puzzle. I’m confused by a regular pattern I observe when I watch others trying to create new communities. They proceed in what appears to me to be a kind of cargo cult behavior. Where they proceed build a runway and then a plane out of old fruit crates. They then you stand back and wait for the manna of vibrant community to fall from heaven. It’s sort of a magic build it and they will come ritual.

For example communities that start by specifying their proffesional behavior (no sleeping with clients), a constitutional document (a vote of 3/4 shall be required for a rules change), a mission statement, etc. Isn’t this backward?

I can’t tell you how many times I have been invited to the launch of some effort and the first the organizers put on our plate is to write a mission statement, or adopt a set of operating procedures. I’m beginning to think this is always the cart before the horse.

I can sympathize. People do this because they are looking for exercises the group can engage in. Exercises that will begin to build muscle. Muscle that represents the groups cohesion. Writing mission statements seems like just the ticket because it looks like it will help the common cause to emerge; and common cause is central to getting a community to rondevous. It just seems that you need to have the Boston tea party before you have the constitutional convention. Party first, constitutional convention second. Best practice?