Conventional wisdom holds that standardization is a means to create increased competition. This is not always the case. Conventional wisdom holds that deregulation is a means to increase competition. This is not always the case. Regulation and lack of standards are two ways that can frustrate the consolidation of small firms in an industry into larger firms.

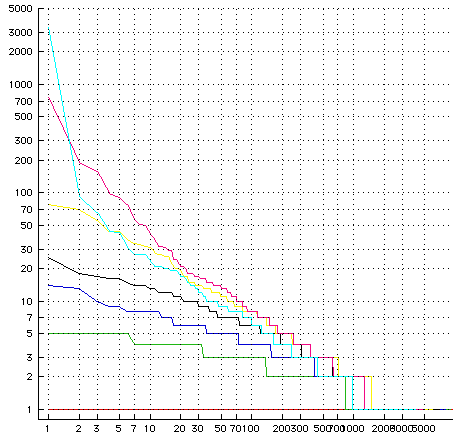

This graph is an output of a simulation of an industry undergoing consolidation. The lines show the distributon of firm sizes in the industry. Each line on the log-log graph is one step toward a more consolidated industry. The line along the bottom shows the industry at the start of the simulation; a ten thousand firms all of size one. As the simulation proceeds firms merge; each merger creates a larger firm. Each line show the distribution of firm sizes after another hundred firms have been absorbed until there are only four thousand firms left; but notice that one of these firms has captured three thousand of the original firms in the market! Now that’s a way to concentrate wealth!

You can see the power-law distribution of firm sizes emerging spontaneously as the consolidation takes place. I.e. this is another means to create a power-law distribution.

Let’s peel back a bit more what’s going on here. This model is based on what graph mavens call a random graph. Each of the original firms is a node in this random graph. To start their are no links at all between them. The simulation proceeds by creating random linkages between these original firms. As links are introduced groups of firms are consolidated into now merged firms; or in graph theory terms you get connected components. Clearly if we do this long enough we will get one giant firm. That is often referred to a a phase transition; in which case we might say that the industry condensed or froze rather than consolidated.

Note that this model creates links between the original firms, so that a firm that is consolidated out of 100 of the original firms is a 100 times more likely to get a random link than one of the original firms is. That creates the usual rich get richer as well as the advantage to the early mover found in the power-law scenarios. The random nature of the linking also reminds us that there is no “merit” revealed by the distribution other than size and luck. Consider what that implies for the sleepy members of an industry the moment that the regulatory (or technological) barrier to consolidation is repealed and suddenly what was impossible before; mergers, are now key to the firm’s ongoing survival.

In the last step in the simulation graphed here you can see that the power-law distribution is on the verge of failing to provide a good fit; the industry is about to freeze up into one giant monopoly.

Both regulation and a lack of standards make it harder to create the random linkages that encourage this kind of consolidation. Something to keep in mind when chatting with the advocates of standards, deregulation, and free trade. Something to think about when large firms argue that deregulation and standards are good for small business. Something to think about when free trade advocates argue that free trade is an unalloyed good for small countries. It is more complex than that.