Steve Jobs makes an argument I’d not seen before about the structure of the music industry. He argues that the industry’s architecture shifts money down the power-law curve. In effect a few a-list performers make most of the money but the industry has happened on a way to see that the money flows down into the b-list. It does this by signing up lots of b-list acts early in their carriers and then funding that expense from the few that make it into the a-list.

Here’s what he says:

After talking to a lot of people, this is my conclusion: A young artist gets signed, and he or she gets a big advance — a million dollars, or more. And the theory is that the record company will earn back that advance when the artist is successful.

Except that even though they’re really good at picking, only one or two out of the ten that they pick is successful. And so most of the artists never earn back that advance — so the record companies are out that money. Well, who pays for the ones that are the losers?

The winners pay. The winners pay for the losers, and the winners are not seeing rewards commensurate with their success. And they get upset.

From a God like point of view this might be very healthy for the industry. An architecture that starves out all your b-list performers isn’t likely to generate a deep pool of talent that occasionally bubbles up an a-list winner. It’s an entirely reasonable deal that’s offered to the b-list players; we make you reasonably wealthy but in the unlikely scenario that you make it into the a-list your going to help fund all your b-list peers.

Notice that Jobs doesn’t say the industry is screwing the performers. He only says that the ones that make it into the a-list often feel that maybe they shouldn’t have taken the deal. He doesn’t say that the industry is stealing the cash the a-list is making; only that they are shifting it down to the b-list.

Wealth redistribution is one of the standard ways that you can temper the power-law curve. There are good reasons to want that. Starving the pool of talent isn’t a very good long term plan. The architecture Job’s outlines is good for the performers; lowering their life time risk and raising their chances of working in the profession of their choice and it’s good for the industry because it creates a more reliable pool of talent to draw upon.

This is the same framework you find inside companies with their ornate job classifications. In any give time frame some high achievers subsidize the salaries of the low achievers in that time frame. Since high achieving is such a crap shoot of variables the structure tends to compensate for the randomness. It spreads risk for both the employer and for the employees.

This is the same framework that union contracts strive to achieve. A degree of tempering the risk in the out years by spreading the wealth across the union members and turning down the capacious nature of the market.

There is a lot of enthusiasm these days for shifting risk out of social structures and onto individuals. There are reasons not to do that. Reasons that everybody involved might well sign onto. I see lots of benefit in societies with a less severe wealth distribution. I find it sobering how fast we are tearing down these structures.

Jobs’ model implies that the a-list performers are bitter about the deal they made. In the context of the music industry they have limited legal options for renegotiating that deal. What’s a pain in the neck about modern politics is that the a-list can renegotiating the terms of the social contract buying enough senators. In the short term this makes the a-list richer, in the long term it starves out the long tail. That’s not good.

Between producers and consumers you need to insert some sort of exchange, a trusted intermediary. I’ve always liked the way that people draw this as a cloud. It suggests angels are at work, or possibly that if you look closely things will only get blurry and your glasses will get wet. Even without getting your self wet things aren’t clear even from the outside. For example what do we mean by trust? Does it mean low-latency, reliability, robust governance, low barriers to entry, competitive markets, minimal concentration of power – who knows?

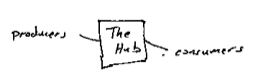

Between producers and consumers you need to insert some sort of exchange, a trusted intermediary. I’ve always liked the way that people draw this as a cloud. It suggests angels are at work, or possibly that if you look closely things will only get blurry and your glasses will get wet. Even without getting your self wet things aren’t clear even from the outside. For example what do we mean by trust? Does it mean low-latency, reliability, robust governance, low barriers to entry, competitive markets, minimal concentration of power – who knows? There are some leading design patterns for working on these problems. Sometimes the cloud condenses into a single hub. For example one technique is to introduce a central hub, or a monopoly. The US Postal system, the Federal Reserve’s check clearing houses, AT&T’s long distance business are old examples of that. Of course none of those were ever absolute monopolies; you could always find examples of some amount of exchange that took place by going around the hub – if you want to split hairs. Google in ‘findablity’, eBay in auctions, Amazon in the online book business are more modern examples.

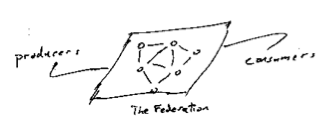

There are some leading design patterns for working on these problems. Sometimes the cloud condenses into a single hub. For example one technique is to introduce a central hub, or a monopoly. The US Postal system, the Federal Reserve’s check clearing houses, AT&T’s long distance business are old examples of that. Of course none of those were ever absolute monopolies; you could always find examples of some amount of exchange that took place by going around the hub – if you want to split hairs. Google in ‘findablity’, eBay in auctions, Amazon in the online book business are more modern examples. Federated approachs are clearly more social than hubs. In markets where the participants are naturally noncompetitive they can be quite social. For example when national phone companies federate to exchange traffic, or small banks federate to clear checks or credit card payments. That can change over time, of course. The nice feature of a federated architecture is that it helps create clarity about where the rules of the game are being blocked out. How and who rules the cloud is part of the mystery of trust.

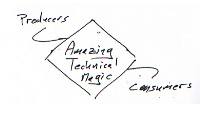

Federated approachs are clearly more social than hubs. In markets where the participants are naturally noncompetitive they can be quite social. For example when national phone companies federate to exchange traffic, or small banks federate to clear checks or credit card payments. That can change over time, of course. The nice feature of a federated architecture is that it helps create clarity about where the rules of the game are being blocked out. How and who rules the cloud is part of the mystery of trust. The magic based solutions have great stories or illustrations to go with them. For example the early Arpanet architecture had each node in the net act advertise it’s service to it’s neighbors who would then shop for the best route – boy did that not work! I worked on on three multiprocessors in the 1970s that had varing designs for how to route data between CPU and memory. One of these, the Butterfly, had a switched who’s topology was based on the Fast Fourier Transform.

The magic based solutions have great stories or illustrations to go with them. For example the early Arpanet architecture had each node in the net act advertise it’s service to it’s neighbors who would then shop for the best route – boy did that not work! I worked on on three multiprocessors in the 1970s that had varing designs for how to route data between CPU and memory. One of these, the Butterfly, had a switched who’s topology was based on the Fast Fourier Transform.

What percentage of the expansion slots on PCs lie empty? 90%, 98%? That’s a lot of empty real estate! Who’s paying for that and why? Think of what all that empty real estate costs to create!

What percentage of the expansion slots on PCs lie empty? 90%, 98%? That’s a lot of empty real estate! Who’s paying for that and why? Think of what all that empty real estate costs to create!