Surely it is not a coincidence that just about the time that western civilization collectively took away the property rights of slave owners it introduced a curious new form of property right: treating ideas as property. Was this some sort of systemic economic substitution? Was that the dawn of an era when content was king? Is that era now entering it’s twilight? Are we seeing observing a similar uncompensated property taking? Will a substitute class of property rights arise?

Category Archives: business modeling

Stock Mnemonics

Taking to heart that ought to keep a eye on the information stream in and about my investments I have place various live or polling queries with various services. From this I have learned that owning a stock who’s trading symbol is a US time zone is a problem. I wonder … it that enough to make this stock trade at a discount? I’m getting a lot of weather reports.

Car Rental & Books on Tape

Why don’t car rental offices have books on tape for me to rent?

Rational Management v.s. Old rich men playing baseball

I finally got around to reading Moneyball yesterday. Any number of people have recomended this book include a number of members of the statistical quality control management cult. My total lack of interest in baseball combined with my minimal interest that management style pushed it far down the stack. But then it was the only book on my list available at the the tiny library I found myself in the other day.

This book is marvalous. Sports provide an ample supply of heros and emotionally charged morality plays. There are so many threads that it’s very hard to summarize. So I’ll just try to pull out some of them.

You could tell this story as being just about how some folks found some inefficencies in a market and proceeded to exploit them. Told this way the tension in the story is why did it take so long for anybody to notice and act on it. The opportunity wasn’t noticed until the 1970s. Why not?

It is also is a story about how a small group of fans, the lowest lifeform in the industry. These fans had a unique talent, a fresh ablity to look at the game coupled with the talents to validate their insights using statistics. The story gets better – when they showed up at then door of the club house with their exciting discovery they are turned away. Just like every other nutty fan has been turned away and has been for years. So they when off and invented a fantasy game that let’s millions of fans begin to see what they saw. Of course to do their analysis they needed data. At first they asked the firms that had the numbers for access. They were told: go fly a kite. So they create a subtitute way to gather statistics. It’s a marvalous example of both innovation emerging at the periphery and how hard it is to get that innovation transmitted into the core.

It is also a story about objective v.s. subjective managment. Which is why the six-sigma guys love it. A story about the slow displacement of artisians by science. It’s a story about cultural blindness and group think. As usual an paradigm unable and disinterested in hearing the disruptive news that a new paradigm has to bring. And thus it is also a story about a proffession grown so insular that is was no longer was striving to disrupt it’s self.

In a marvalous complement to those stories the author selects as his hero somebody that crosses between the two camps. A man burned by the old system. He sold his life to the profession as a boy and they did him wrong, or at least it didn’t turn out well. In a lovely personification of the subjective/objective tension of the peice he is nearly unable to keep his subjective passionate side in control. But, having been burnt by the proffesion’s old men he embraces the new objective methods. It is the story of an angry man forcing a rational management framework down the throat of an industry run on traditions that have that having lost their objective grounding are now just just emotion and intuitions.

From that it become also a story about this middleman. The hero is the two faced middleman. Bridging the market failure the talented fans on the periphery uncovered. This is key. You couldn’t use the new tools unless you could play by the old rules. So, for example, they figure out that the prices of relief pitchers are inflated, better yet the stats used by the old paradigm are easy to manipulate. So they can pump up a guys stats and sell him off at a tidy profit. Of course when you sell him you have to be able to present him exactly in the manner of the old paridigm. Our hero the middleman can do that; he lives and understands both paridigms.

The story is also a facinating story about the evolution of the industry’s architecture. The industry was built to assure that extreme variation between teams would not emerge. No power-law here. To do that the industry has adopted some standard devices for smoothing out inequality when it emerges. Lousy teams get first pick of new players. Players are tied to the teams with multiyear contracts, that tempering the ablity of rich teams to aggregate all the proven talent.

That architecture began to fall apart when the players (labor) managed to convince the courts that they were getting screwed by the owners (capital). The moment that players got freed the rich teams began to aggregate talent. Players were right, they were getting screwed, and their salaries rose by huge factors (10, 100). That money came from two places. Owners and fans; mostly from the fans since of course they are the ones with the least power in the industry.

The break down in equality producing architecture (wealth transfers, and regulatory devices) lead enivitably to increasing inequity in the game. Pretty quickly the salaries paid by various teams became expodentially distributed, but not power-law. In a subplot I find highly ironic a blue ribbon commission put together to study this growing inequality found it’s most politically conservative member, George Will, arguing that the breakdown of the architecture of wealth transfers and strong regulation was certain to kill the sport. Was he being a traditionalist, or a pro-capital anti-labor I wonder. Whatever, I’m sure he was blind to the irony that what he was advocating in the sport he was railing against in the society.

So then there is a thread about how it all plays out as the existing industry architecture falls apart. The incentives to break with the common consensus of the existing proffesionals strengthens. When the teams were, by design, closely aligned in talent the industry’s firms could collaborate as peers. That created a gentlemanly climate in the industry. Scouts, for example, would reach a industry wide consensus about incomming talent. Owners, not under strong competitive pressure, prefered stable rules sets to innovative risky ones.

As inequality sweeps into the industry a dynamic emerges. The losers, the guys out on the tail, discover that they have less and less to lose from experimenting with radical approaches. If your at the bottom paying your talent a third or a quarter times what the guys at the top are paying your chance of winning becomes nothing more than a fantasy. Like the millions of fans playing fantasy baseball you start to notice, what the hell, let’s try some experiments. Finally, and it took a surprising long time, one of them tried the experiment of using the radically better approach that the statistics nuts in the fan base had uncovered.

At this point you get the heart warming stories. Undervalued players the one the old paradigm wouldn’t touch are raised up. They are terribly grateful. When Mr. Fatty get’s the call from the new experimental team it’s the best day in his life. The old paradigm was oppressing these guys and the new paradigm is rewarding them. Sweet huh?

Some huge innovations create huge new businesses while other innovations don’t. What distinquishes the two? The ablity of an existing industry to take the innovation onboard. If the existing gorrilla’s in an industry can absorb the innovation then they do. If they can’t and the innovation is big enough then you get a huge new firm. For example Paypal is too risky a payment’s model for the credit card company’s to swallow.

Of course if they chew long enough then even the most difficult to swallow changes can get absorbed. Big firms have lots of time and resources to chew with, for example, the American auto industry did learn at least some of the lessons from the radically different way the Japanese auto industry operated. Even if it took them 25 years.

I have no idea how long it will take for major league baseball to swallow this innovation, but for a while it helps to temper the inequality between teams the current architecture creates.

Phone Payments

Reading something about payments in a 3rd world country I’m struck by the presumption that their infrastructure will look like ours. Their phone infrastructure doesn’t. Resource limits are sure to make much of their infrastructure different than ours. Finally currency substitutes exist only because the state has relinquished some portion of the job of managing the currency. That means that there are a huge range of alternatives depending on how the state manages the currency system. If the state fails to provide a dependable (which includes highly and electronically fungible) currency then currency substitutes then substitutes will arise – scratch cards for example.

It seems to me that cell phones totally change the game. To people with cell phones can obviously use an intermediary to broker a transaction. The buyer gives the celler his an id #, the buyer then sends an SMS to the intermediary with that # and the amount of the transaction. The intermediary then sends an SMS to the buyer with the authorization code which he gives to to the seller. etc. The barrier to establishing this infrastructure small and the per message costs of SMS low enough. Of course it would be better if the buyer didn’t hand over an id # but that would require either training, more message exchanges, or some modification to the phones.

Payments at the bottom of the pyramid, particularly in the presence of weak states, look to me like a very interesting problem domain.

Wealth in the long tail!

Friction and the new dark ages

This article from the WSJ is interesting, it’s about using systems like pubsub to create persistent search as part of trying to get as far in front of the rumor mill around your investments as possible.

“It’s like a giant electronic driftnet,” …

Such technology may have been at work recently, when the results of a government study of a cancer drug developed by Genentech was mistakenly posted on the Web site of the National Institutes of Health. An hour after the results went live, the stock had soared nearly 20%. David Miller, president of Biotech Stock Research, based in Seattle, said a few investors using the new technology may have seen the change on the NIH site, which put the release on its RSS feed about five minutes after it appeared on its news page — and acted on it.

I really like that driftnet metaphor. Very synergistic with my talent scrapping metaphor; or that some business models are like whales.

Fun to puzzle how about how friction is always part of the market/business design. As King Content continues to be dethroned by the distribution channels the net present value of content falls. Like money in a depression it’s interest rate is going negative. When the interest rate goes negative the incentives get pretty strong to pull the money out from under the mattress and convert it into some other capital good. Presumably that’s what’s happening to content.

So maybe I’m wrong.

I’ve been assuming that open content and owned content are in a death match. That open content will win. That the displaced culture around owned content will go dark. I call this the new dark ages – that all the content copyrighted during the 20th century will just go dark. Locked up in the vaults of the mega-content owners.

But, just maybe, like those who horde capital in a recession the content owners can be convinced to pull it out of the vault. No wonder these guys are doing everything they can to increase the friction in the information distribution networks!

El Curve

I’m thinking that it might be more useful to use the term El Curve rather than Long Tail when we talk about the things with a power-law like distribution. Long tail is a useful term when our focus is reaching out into the long tail; but it frames the discussion in a manner that ignores the role of the vertical portion of the distribution in the architecture of the systems we build.

I’m reading the cheerful provocative book “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid,” which is about this very question. How can we architect business models that span from the vertical edge down into the horizontal edge to create economic growth thru-out. The book is targeted at the leaders of multi-national corporations. It wants to sell them on the idea that selling into the long tail of the world’s poor is a great business.

Without question the most politically charged power-law curves are the distributions income/wealth curves. The data is sobering. If I pluck the data out of the book’s pyramid drawing and split the world population into two camps about .1 Billion (1.7%) make more that $50 dollars a day and 5.5 Billion make less. It’s easy to become hysterical.

This book declines to partake of that temptation; his audience doesn’t respond well to that. Instead it’s a set of case studies in classic B school style along with the grand rules of thumb required of such books.

The business models all involve elements all along the power-law curve. A distribution channel if you like, though he calls it a process design. Value generating activities along the curve are orchestrated by the firm that designs, builds, and owns a economic network implicit in the business models. This is analagous to the way a fanchise resturant chain architects a value chain that reachs from the individual store up and into centralized production and marketing facilities. Like all economically stable systems some customer problem is resolved and value is captured in exchange for solving the problem. The captured value is spread along the various stages along the power-law curve.

This book is facinating if your interested in business models that reach into the long tail. In spite of it’s overwrot enthusiastic MBA tone, I’m enjoying it.

Advertising Channels

I was raised by wolfs, well academics actually, and so it was only very late in life I learned that all stories are required to have three legs: problem, hero, and movement toward resolution. The power of this rule is demonstrated by how far some authors will stretch to fit. An example is a piece in the current New Yorker. Where the heroine is an advertising professional, and her problem is the end of the Golden age of advertising.

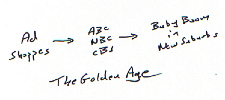

To hear tell in the golden age of advertising little shoppes of advertising artisans lined the streets of Manhattan. As the curtain rises, desperate mouthwash manufacturing mogels would travel to this village and step into one of these shops. He would, of course, be carrying a few million dollars. In the second act the shop owner would craft a campaign and place it on the three television networks. In the third act the American public would tune and discover they had an unfulfilled desire to gargle more. As the curtain goes down they are all placing bottles of mouthwash into their shopping carts at the A&P.

To hear tell in the golden age of advertising little shoppes of advertising artisans lined the streets of Manhattan. As the curtain rises, desperate mouthwash manufacturing mogels would travel to this village and step into one of these shops. He would, of course, be carrying a few million dollars. In the second act the shop owner would craft a campaign and place it on the three television networks. In the third act the American public would tune and discover they had an unfulfilled desire to gargle more. As the curtain goes down they are all placing bottles of mouthwash into their shopping carts at the A&P.

This golden age amuses me. On the one hand you have numerous little firms and on the hand you have three huge television networks. It’s the canonical industry structure. On the one hand you have a highly consolidated distribution channel and on the other hand you have a long tail of tiny producers. In the nostalgic telling this is a beautiful thing. The small firms were wonderful because it they gave free reign (free-range?) to the heroic creative folk. The big networks were wonderful because they had aggregated the audience in a so convenient a package that it took one dance number late in the second act to deploy your campaign. During this scene money would rain down upon the stage.

To hear tell the golden age has ended. The advertising industry has condensed. The entertainment industry is more of a slush.

The article fails, in the end, to fit the required story template. The article is reduced to an enumeration of the various species emerging in the genus advertising. Not that, a kind of butterfly collecting, is something the child of academics can appreciate.

Here’s an interesting butterfly: 20 seconds of in-show product placement costs about the same amount as a 30 second ad. I would have assumed it costs more. About 40% more is spent on internet advertising than on product placement, but both are growing fast. Here’s another butterfly: Some newspapers are custom printed at the granularity of the postal code.

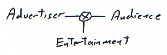

Distribution channels fascinate me. Part of my fascination is the way they are fundamentally two faced; the distribution firm must balance between two strong forces. So an entertainment/advertising channel is trying to find a balance between the desires of it’s advertisers and the desires of it’s audience. Actually it’s got three faces, which is even more fun, but let’s gloss over that today. This tension is the ecology within which these butterflies evolve.

Distribution channels fascinate me. Part of my fascination is the way they are fundamentally two faced; the distribution firm must balance between two strong forces. So an entertainment/advertising channel is trying to find a balance between the desires of it’s advertisers and the desires of it’s audience. Actually it’s got three faces, which is even more fun, but let’s gloss over that today. This tension is the ecology within which these butterflies evolve.

Bewitched, the old sitcom about an ad executive living in the suburbs married to a witch, must be the perfect example of what emerges from an environment with such forces. It’s a show about the customer on both sides of the advertiser/audience channel! And, it is also the perfect venue for product placement.

The channels in the advertising universe – defined by the advertisers and audience it attracts – must strike a balance. Here’s another butterfly: the article tells a story of a TV show in which one of the characters takes a job pitching a product at the local mall, his pitch is identical to the ads spots broadcast with the show.

Billions and billions of ad channels are emerging. Google’s adsense is an example of that. That creates a bloom of new species of advertising channels. Some venues try to maximize how much they serve the advertiser, some try to maximize how much they serve the audience. Some venues don’t even choose to play in this game. The nostalgia for the golden age of advertising is the usual nostalgia for a time when the rules were well understood. The networks defined the audience and the manufactures and advertisers created products and campaigns to fit. Diversity is so confusing.

Developer Network Pricing

One of the mysteries in business modeling is how to do pricing, or any financial modeling, for your developer network offerings.

Developer networks are a marketing channel. Firms create developer networks to encourge 3rd parties to create products that complement their core offering. The presumption of these efforts is that the complementing products will increase the overall value of your offering. Businesses that use this approach refer to their offering as a platform, network, or toolkit. There are probably other names that get used. If you know some please tell me.

The puzzle around the pricing has three parts. First – Pricing provides a feedback, a signal, and if you subsidize the pricing how do you know if your actually generating value? Second – if you subsidize the price the firm automatically treats the developer network as a cost center rather than as a profit center. The standard way to manage a cost center is cost control; and that leads to the brilliant insight that if you shut down the developer network you save money – and that can’t be right.

The third problem is one of time and distance. The model that developer network leads to compliments and that leads to an increase in core offering value is all well and good. It’s not hard to pile on additional bits of optimism. A successful complement will create sales for the core offering. A rapidly evolving innovative new complement will force upgrades for the core offering. The third problem is that these feedback loops are very long and very diffuse. Or in Net Present Value terms they have high hurdle rates and low present value because they are, well, out there. This is a kind of options pricing problem.

So when I look at Microsoft’s recent pricing changes around their developer network I read into some conclusions. First – their management has fallen victim that ever popular fetish – market are the best model of any system – and are forcing the developer network to tie it’s self more tightly to a pricing signal. Second – that they have broken up the company in ways that treat the developer network more as a cost center and less as a marketing channel.

The third thing it appears to say is the most interesting. I believe that Microsoft is one of the few places with a financial model that can solve the options pricing problem. So raising their price maybe a signal that either they lost the model; or that the model is generating a less positive output. Climbing even further out on a limb. I think the model says that fewer developers are taking them up on the the offers implicit in the developer network offering, they are loosing developer mind share.

In summary, I see the raising of prices Microsoft developer network prices, as a the sign of weakness in their developer network business. That is really really bad for for a platform company.