Programming languages often have a juicy core of one kind or another. Back in the 60s and 70s we had a lovely assortment of languages each of which took some particular idea to heart and then ran as far was they could with that idea. SETL – using sets – is a good example. It was a lot of fun to write within it’s framework. I still my delight when, at one point, they managed to get the compiler’s optimizer to the point where it spontaneously discovered assorted famous graph algorithms.

Programming languages often have a juicy core of one kind or another. Back in the 60s and 70s we had a lovely assortment of languages each of which took some particular idea to heart and then ran as far was they could with that idea. SETL – using sets – is a good example. It was a lot of fun to write within it’s framework. I still my delight when, at one point, they managed to get the compiler’s optimizer to the point where it spontaneously discovered assorted famous graph algorithms.

Other examples include:

- SIMULA – using what we’d now call lightweight threads.

- SNOBOL – centered around pattern matching which informed a whole tangle of other languages like SL5, and Prolog, and such.

- LISP – with its symbols, lists, etc. etc.

- APL – with its arrays

- etc. etc.

There others that stand atop a big data structure; SQL, Emacs, and AutoCAD.

Some stand on an unusual computational model. Rule based (truth maintenance?) systems like Unix make or Prolog. The constraint based systems. Lazy evaluation.

A very few are almost only about some syntactic or semantic gimmick; like forth, postscript, or Python.

Is that era is largely over? The search space has been mined out? I guess some work on genetic programming or machine learning are the modern decedents of this style of language design.

All these languages have a kind of inward looking quality to them. They don’t really care much about their users. If there are applications, well that’s nice. Their enthusiasm is rooted in their the juicy (often somewhat eccentric) center, not the tedium of actually putting them to use. To a greater or lesser degree you can make that critique about all programming languages.

Which brings me to a last night. Harry Mairson gave a nice little talk to the Boston Lisp meeting about a spin off of his hobby – which is making string instruments.

Which brings me to a last night. Harry Mairson gave a nice little talk to the Boston Lisp meeting about a spin off of his hobby – which is making string instruments.

Apparently we don’t actually have a good handle on how our ancestors designed and built their instruments. Insta-theories might include that they traced existing instruments, or maybe they had templates they handed down, etc. etc.

One recent theory is that they had recipes that guided the making of patterns using only compass and straight edge. There is a book that makes this case. “Functional Geometry and the Traité de Lutherie.”

When Harry found and read this book he got to wondering if the descriptions in the book might be converted into something more algorithmic. He spun off a little language where the juicy core was a compass and straight edge. … time passes … and now he can write programs that almost sketch out the designs for cellos and such. It was an awesome, eccentric, fun talk.

It’s notable that he did this backward. He started from the application and ended up with a cute new language based on a curious juicy center.

I found myself wondering. To what extent the design languages used by craftsmen in the Middle Ages rested on the compass and straightedge. Architecture? Furniture? Music? Here’s graphic I found showing a bit of (presumably modern) font design.

His work is not yet published, so all of you who are suddenly tempted to write a web server using only a compass and straight edge are best advised to wait until it is.

Update: Cool, there is now a paper you can read. I look forward to seeing your web servers.

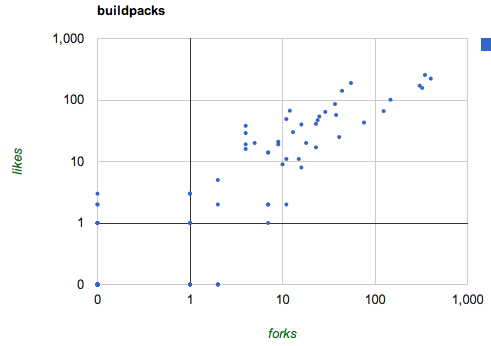

John Siracusa has posted a quite thought provoking piece about the power games unfolding between Google, Apple, Facebook and others. Let’s say you wanted to own a cirtical open source project, i.e. own a key standard. How might you go about that. He makes a case, that has some merit(sic), that contribution rates can be used by a firm to buy control of an open source project. If so, then it’s only a matter of money and time.

John Siracusa has posted a quite thought provoking piece about the power games unfolding between Google, Apple, Facebook and others. Let’s say you wanted to own a cirtical open source project, i.e. own a key standard. How might you go about that. He makes a case, that has some merit(sic), that contribution rates can be used by a firm to buy control of an open source project. If so, then it’s only a matter of money and time.