Category Archives: business modeling

Blog Payolla!

A fun article in a recent the New Yorker about a radio station in New York City mentions in passing that Eliot Spitzer the NY attorney general is currently investigating a bunch of radio stations for taking payola. I’m kind of glad, if surpised, that there are still consumer protection laws on the books about that.

Meanwhile bloggers can now take payola, see over here.

This article about blogger payola is wonderfully ironic once you notice the amazing assortment of advertising techniques in use by it’s web site.

Network Neutrality

I’ve not been following the net neutrality debate, so I presume all these points have been made by others. But I want to firm up my thoughts, just for fun.

There are a few frames you might map this into.

The traditional telco regulatory framing is about monopoly power v.s. the little guy. This framing the monopoly power of the telco arises from network effects and physical realities. The state steps in to help coordinate the creation of the monopoly; handing out one of a like license for airwaves and utility poles. The state also steps into limit the perfectly natural tendency for capital to abuse thier monopolies at any oportunity. This framing is all perfectly valid; etc. etc. In the current US poltical ecology it also write it’s own outcome. Capital wins, the little guy looses; an any public good is converted to a private good in the hands of the highest bidder. The only question is who runs the auction; the state or the legislators.

A second frame to drop this debate was nicely coined by Martin; ‘What’s the label on the tin?” Markets work smoothly, scale up quickly, and generate lots of wealth and externalities when the transactions can be executed quickly. That requires setting standards; those standards reduce what aspects of each transaction you need to negotiate. The state gets involved in these debates because of it’s unique power to set standards. Markets participants have a love/hate relationship with this standards making process. They love it because in the best scenarios everybody wins; and they hate it because during the game individual actors can sometimes capture huge benefits for their class of actors. You can predict which standards battle will be long v.s. short using various means. In this case I’d predict a long drawn out battle.

Yet another frame we can drop this into is old v.s. new capital. The distinquishing characteristic of old capital is that it tends to be much more politically connected and conservative. New capital has weak political muscles; since while it’s got them it hasn’t practiced using them. In this story we cast the telcos in the role of old capital and the new web businesses in the role of new capital. The new guys are a complementary industry of the old guys. The old guys would like a peice of the action. So they are looking to get the power to charge the new guys to deliver content over them. This frame predicts that the key question is can old capital move fast to lock-in advantagous regulations; faster than new capital can figure out how to use those untrained political muscles. I think that’s obvious new capital will learn quickly enough. That’s clear because they have common cause with some other large players: media, device makers, and software plaform vendors. Those three already played a round in this frame during the HDTV standards battles. If we presume that then we can also predict that this standards battle will be quite drawn out. Two very wealthy industries competing for the state’s attention is not a recipe for a quick resolution. Bearing that in mind I read this report as indicating that Alen Specter has recognized that could generate a lot of campaign contributions for a very long time.

It was unclear precisely what approach the Judiciary Committee would take. Specter, for one, indicated that he would prefer looking at the issue on a “case-by-case” basis rather than issuing a “general rule” about what network operators can and cannot do–an approach favored by Internet companies. He said it may be more productive to negotiate less formal “standards” for network access with the players involved because writing new laws is “extraordinarily difficult, candidly, when you have the giants on both sides of these issues.”

The final frame I notice in this discussion is how the telco industry is undergoing a very very fundimental shift. The telco industry does distirbution or brokage; like roads, canals, airlines, UPS, eBay, match makers, etc. Traditionally they transported phone calls; one end you place the call, the other end would recieve the call. Note how there are two kinds of actor there; that’s true in all these industries. If you and I play in both roles from day to day – we make calls, and we recieve calls. There are different labels for the two roles. In the internet we call them client and server. At eBay and other markets you call them buyer and seller. The match maker calls them wife and husband; or employee and employeer. The media industry calls the content producers and consumers. Most of the new capital businesses, ebay, google, etc. have very sharp distinctions between the two roles. They often charge one side and the other; and they always have very different pricing schemes for the two sides.

Telco is a interesting case, because historcially it had a reasonably weak two sided network nature. That’s changing, and fast. The emergance of the large web properties who serve vast populations of users means the telcos are now two sided businesses; but only if they can get the regulations written when they weren’t revised to allow them new forms of pricing power.

This frame has some hints in it about how what I suspect will be a very long drawn out standards/regulatory battle might be resolved. This is about how to label the tin; and both old and new capital find that a very puzzling problem. I’m bemused by the thought that the giant web properties might remain “free” by having the telco’s pay them; which is more or less the model uses in the cable TV industry. It’s an ugly outcome; but it’s consistent with the current political ecology; where the little guy doesn’t even have a seat at the table.

The Liablity of Sowing one’s Oats Widely

This is great…

In a sense, Google, in its ADD-driven style, is building up a sizable engineering liability here, one that it will eventually have to ‘fess up to.” — at Infecious Greed

Is it true? For the life of me I don’t know.

Network effect businesses depend on running as fast as you can to capture a large a network as fast as possible. This is amazinlgy risky balance between capturing share and avoiding “engineering liability.” Nobody knows the right balance but we do know the trends. The share v.s. low-risk dial has moved consistently toward share wins. Microsoft’s ship crap fix it later strategy got them thru the transition to GUI, and quite a few other company killing upheavals. Open Source’s ship early and often strategy has enabled it to capture installed base and hence set standards faster than more conservative tactics.

I suspect that the author of the quote above is just peeved that he’s locked into more and more Google offerings while being frustrated that they aren’t becoming the robust software he desires. If these products were open source he could join in common cause with his fellow travelers and fix them. But since his vendor is a monopolist his only option is to plead, shame, and otherwise use voice rather than doing to resolve the problems.

The Perception of Risk

Another fun item from Chandler Howell’s blog about how people manage the risk. People try to get what they percieve to be the right amount of risk into their lives, but they do this on really really lousy data. So there are all kinds of breakdowns.

For example you get unfortunate scenarios where actors suit up in safety equipment, this makes them feel safer so they take more risks and after all is said and done the accident rates go up. Bummer!

I’ve written about how Jane Jacobs offers a model for why Toronto overtook Montreal as the largest city in Canada. After the second world war Toronto was young and niave with a large appetite for risk; while Montreal was more mature and wise. To Toronto’s benefit and Montreal’s distress the decades after the second world war were a particularly good time to take risks and a bad time to be risk adverse.

I’ve also written about how limited liablity is a delightful scheme to shape the risk so that corporations will take more of it. All based on a social/political calculation that risk taking is a public good that we ought to encourage.

What I hadn’t apprecated previously is how this kind of thinking is entriely scale free. Consider the fetish for testing in many of the fads about software development. The tests are like safety equipment, they encourage greater risk taking. Who knows if the total result is a safer development process?

IP Piracy – the business model

Nice sophisticated article from the Business section of the LA Times about how it appears that they are very conscious that software piracy is good for Microsoft.

“They’ll get sort of addicted, and then we’ll somehow figure out how to collect sometime in the next decade.” — Bill Gates

I’ve written about that before both here to illustrate how exactly the pirate price appears to be set and about how some nations might prefer to enforce IP rights to as a form of classic home industry protectionism.

I particularly like this quote from an IP lawyer.

“Is widespread piracy simply foregone revenue, a business model by accident or a business model by design?” he asked. “Maybe all three.”

I love that because when your firm is executing on a model like that it becomes totally keystone cops inhouse with people running in all directions. The article outlines how the people who are chasing lost revenue managed to encourage adoption of free software in the Islamic world.

The effort even prompted Islamic clerics in Saudi Arabia and Egypt to declare fatwas, or religious edicts, against software piracy.

I have no doubt that if Microsoft could strictly enforce their software licenses that would be great for open source. It would raise barriers to entry high enough that the majority of users on the planet could not get over them. Given the necessity of regular security patches it is also clear to me that Microsoft is intentionally not enforcing their licenses.

Private Currency Systems & Ebay

EBay recently posted a policy for payments that, using their power as market makers, regulates the currency substitutes which sellers are allowed to utilize for their transactions. It’s an interesting read. It provides a pretty wide ranging tour of some of the ways people have found to create currency substitutes.

For example I just love this section where precious metals and frequent flier points are lumped into one category “… payment model involves precious metals, or other non-cash (points, miles, minutes, coupons, discounts) …” who knew? At that point I’m find I’m wondering if people are actually selling things on eBay in exchange for long distance minutes and loyality club points?

I’m amused that eBay has declared cash to be verboten. In effect taking the default currency system and eliminating it as a competitor for PayPal is clever. They frame it up as about safety, but of course it also has consequences on anonymity and transaction costs.

Private Currency Lost in the Sofa

It’s hard to get a handle on all the ways that a private currency operator can profit from his franchise. But one of my favorites is having the loose change slip between the sofa cushions never to be seen again. The accounting rules for these things must be a mess. One of the reasons why the folks that issue gift cards like for them to expire is somewhat like the reason why firms like to make your vacation time expire; otherwise they have to do something to keep it on their books.

So today Home Depot announced it was going to claim 50+ Million Dollars that it’s pretty sure it’s customers have lost in the sofa since they bought them.

The article also reports that $55 Billion dollars moves into the private currency systems call gift cards every year; it doesn’t estimate how much manages to get back out v.s. slip into the sofa. I find that number a bit bewildering; there are 100 million households in the US; or so that’s $550 per household. I presume that the distribution over households is skew’d (since that’s my default presumption for distributions involving exchanges). I can imagine that there are people who build entire houses via gift cards; but still! Most of the gift cards are capped to hold only a maximum of $500; so it must get pretty weird for the high volume gift card users.

But wait. The article then goes on to find an source that thinks that if you take the bank issued gift cards, i.e. Visa/Mastercard gift cards, the annual amount might be up around $100 Billion; at which point we are talking a thousand per household. The bank cards are more fungible so I suspect some of those get shipped over seas; then possible some of the regular gift cards do too?

“spokesman for … Best Buy. ‘We really believe gift cards are all about convenience.'” What he means is, of course, they is very very convienient for Best Buy.

patriots, not mercenaries

In one of my mailing lists somebody brought this one liner to our attention: “We want patriots, not mercenaries.”

The topic was outsource your firm’s IT operations. That really helped me crystalize something. IT is so central to productivity and positioning in the modern firm that there is something quite odd about letting control of it slip into the hands of vendors.

One of the reasons open source can work is because it substitutes an alienated cash/contractual relationship for a richer collaborative one. This enhances the chances you don’t loose control of such a key component of the modern firm.

That, by the way, was the royal we so common inPR personality puff peices.

Payment Network Cost Trends

The new issue of The Review of Network Economics has a pile of articles on payment networks. The last “A Puzzle of Card Payment Pricing: Why Are Merchants Still Accepting Card Payments?” (Abstract)of which takes a run at the question of how loyal the merchants are to these networks by looking into the puzzle of why they haven’t been dropping out of the networks in droves given the rapidly rising prices.

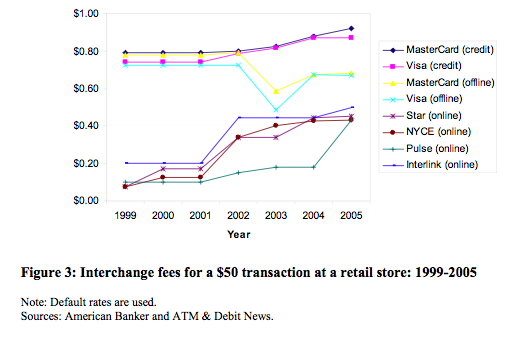

The number plotted on that graph is the price charged by the network to clear a transaction thru the network. It’s set by the network operators. This market is sufficently concentrated that those operators can signal to each other and as you can see their prices move in lock step. The only dip on the chart was do to a court case where two of the networks were accused of abusing their market power.

That chart does not show the prices merchants and consumers, the two sides of this network, actually pay since there are usually a number of intermediaries between them and that clearing house. When you add in those fees the question becomes yet more puzzling. It’s not just price that makes this an interesting question. Presumably Moore’s law and his friends have cause the cost of these networks to drop precipitously.

Clearly these merchants are extremely locked-in (or loyal if prefer that framing). These networks have accumulated a lot of market power.

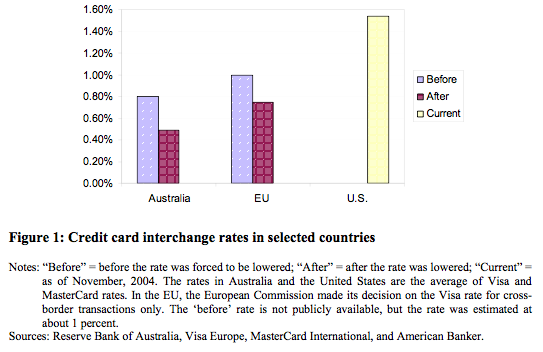

I frame this up as a question of competition between various currency systems. In particular a competition between private currency systems run for the benefit of the currency system operator v.s. state run systems run for the benefit of those who govern the state. The question the paper is trying to puzzle out an answer to is actually asking the question why do merchants not abandon the private systems in preference for the state run systems? The short answer, at least in the US, is that the state run system isn’t even a player in the game anymore – i.e. it doesn’t compete. The second chart shows that in other regulatory environments the state has used it’s power to limit the power of the private systems to tax the system.

Both the private and state run currency systems have complex governance systems. An merchant or consumer (either individually or in groups) has a lot of options for how to negotate with these systems. Consider a consortium of giant merchants. They could go to Washington and lobby for more regulation so assure that the falling costs are passed thru which would increase their sales. They could go to the courts, as they did when some of the fees dropped in the first chart, and argue that market power is being abused. They could go, and i assume they do, to their banks and demand price breaks.

There are lots of different ways the reduced costs can be passed thru to the different players. Not suprisingly when the costs drop the first player to grab them are those closest to the place where the costs are falling – i.e. hub operator.

I use a credit card that pays me 1% back on all my transactions. That makes me much much more likely to pay with a credit card rather than cash. That’s a beautiful example of how these games are played. Technology gave the payment networks lots of options. When they took this one, i.e. offering cash back credit cards, they used their market position to shift costs from consumers to merchants in a way that increased the loyality of hard holders to the private currency system. That in turn made it harder for merchants to decline the cards. It took the payement network operators a few years to discover that 1% was sufficent to buy the loyality of most of their customers; there was a fun period when I had a card that returned 5% on all my purchases.

Interesting to me is how hard it is to get the benefits to spread to the small players; i.e. the corner stores run by small businessmen. Note that if the large merchants go put the squeeze on the network operators and negotate lower costs they actually prefer an outcome that creates a disadvantage for their smaller competitors. Examples like that are why I’ve become suspicious about claims that technology empowers small actors more than large ones. I’m coming round to thinking that it’s an important driver of the depressing shifts in the distribution of wealth.