A portion of City: Urbanism and Its End by Douglas Rae bears retelling.

A portion of City: Urbanism and Its End by Douglas Rae bears retelling.

Rae argues that cities solved a coordination problem, but only for about a century bringing together energy, industry, transportation and labor. That century started around 1850 and ended around 1950. Everything changed. The car and truck displaced the railroad, so factories could be sited outside of the urban core. Electricity displaced coal so that you didn’t need to be sited near flat water to get your energy supply. Telecommunications displaced physical presence so the need to be collocated declined. Television and the melting pot displaced the motivations that held sustained a rich fauna of civic organizations. Industry consolidation – into national rather than local firms – broke the common cause between civic and commercial interests. Hobbled city government, an American tradition that cities are particularly crippled by since they exist only at the pleasure of their state governments, meant cities could not effectively react to those changes. He makes a very convincing case for all of that.

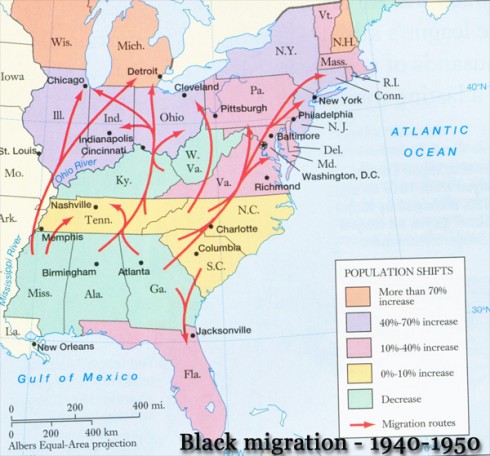

But the story that bears repeating is about the black migration out of the South and into the Northern cities. It’s timing could not have been worse! He calls it horrible. Just after the cities had begun their decline the migration picked up. They moved toward the economically vitality centers, but it was too late. Those centers were already imploding. What that means, among other things, is the usual story of white flight is misleading. Urbanism was evaporating and the black migration moved into those urban centers just after the trend had become unstoppable. They moved into what was soon to be an increasingly empty carcass, abandoned.

Sort of like: buying real estate at the peak of the recent bubble, moving to Boston just as the mini-computer industry lost it’s way, or moving to Montreal just after the 2nd world war. Timing is really hard.