I wish to take issue with this essay disintermediation on Ad Age. It’s really pretty good, but it’s more fun to rant. Here’s a pull quote:

But the truth is, the products that are threatened by disintermediation are not imperiled because of technology; they are imperiled because they are based on models that offer less value to the customer than competing alternatives. In example after example, the middleman isn’t being cut out. He’s simply being replaced by a better one.

This is worth repeating: What we have grown to call disintermediation is, at the end of the day, simply the cold reality of someone doing our job better than we are. If you sense the cold breath of “disintermediation” on your back, more likely than not a bunch of upstarts are delivering your business’ core value proposition for less cost and in a better fashion than you are. And while it seems a bit obvious, it’s nevertheless true: You’ve probably fallen victim to old Railroad disease – you thought you were in the train business, but meanwhile, the other guys have figured out a better approach to moving cargo around the country.

That’s misleading.

Intermediaries are like bridges over a river. They provide the populations on either side of the river a means for getting to each other. The newpaper for example provides a bridge between advertisers on one side and consumers on the other. The marketplace provides a way for buyers and sellers to find each other, transact their business, and clear the resulting books.

The event of disintermediation is always associated with somebody building another bridge. If you own a bridge, lucky you, then new bridges are a threat to your business. Technology both enables new bridges at lower cost, but it also makes it easier for customers to reroute their behavior so they can use the new bridge. To say that the bridge owners are “not imperiled because of technology” is bogus.

A bridge is a huge capital asset that owners typcially spend long time and effort to acquire. For example ClearChannel here in the US spent a lot both thru political manuvering and acquisitions control a large chunck of the nation’s radio stations. They did that because they viewed that channel (bridge) as a powerful intermediary that they could charge a nice toll for folks to travel over.

If you own an a large expensive asset it’s a good idea to keep I eye on how hard it is to build a substitute. What made the asset expensive in the past is often not what makes it hard to reproduce today.

Maybe the railroad guys were blind to how automobiles were going to substitute in the role of cargo handlers, but I doubt it. The railroads substituted for canals. And all three, canals, railroads, and highways arose as substitutes thru the usual combination of government support and technology. This story has been going on for a very long time.

When the new bridge appears it offers some set of features. Those features, compare to those of the older bridge, are better than the existing bridge. Over time customers see that and start to give a portion of their business to the new bridge. So yes the old bridge owner can look at that as “simply the cold reality of someone doing our job better.” That’s true but terribly incomplete.

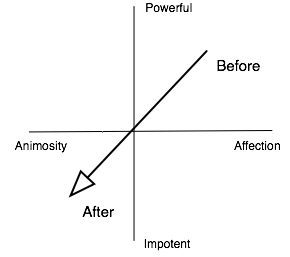

The new bridge changes the nature of the market. It reframes the measures of quality for the market. This usually causes the market to get larger. It always causes a huge disruption in what the definition of quality is. The old bridge owner hardest puzzle, when the new bridge open up, is shifting from a world in which he knows what quality means into one where it’s up for grabs. The new entrants want to redefine quality, pulling it toward what ever is to ther competitive advantage. These advantages are likely a direct fall out of what every force in the environment enabled them to build their new bridge. Again that’s often technology – though it can just as likely be a shifting regulatory climate, demographics, etc.

While the essay’s blith setting aside of the role of technology is what first pulled my cord, it’s this second more subtle failing that I find more problematic. The essay ends up advising the old bridge owners to return to their roots, to retreat back into their comfort zone, as they look for the key source of qualities to emphasis as they adapt to opening of a bridge next to theirs. This is a bit like advising them to put a new coat of paint on the snack bar next to the toll booth and send the toll collector’s uniforms out to be laundered. It’s what they want to hear, but it’s not what they need to understand.

Old bridge owners rarely become irrelevant, in fact they often continue to grow. After the dust settles the old bridge owners find they are in a market who’s consensus about what attributes define quality has changed. Attributes that define quality are not an absolute. In one time frame quality maybe defined by safety, while in another it maybe defined by price, and then later it maybe defined by convient availabity. If the old bridge owner is to remain on top, in market share terms, then he needs to shift his value proposition toward the newly emerging attributes and depreciate the ones that used to be critical.

When the definition of quality changes the market becomes extremely confusing. It is some comfort for the old bridge owner that the new bridge owner probably doesn’t understand what the new rule are either. The new bridge owner leveraged an oportunity given to him typically by technology, but he doesn’t know what qualities his customers care about – he just has some guesses. But the new bridge owner has something of inestimable value in working out what the answer is, customer contact.

The article that triggered this rant is interesting. It does, to a degree, advise the old bridge owner that he needs understand what the emerging quality vector space is. But it pretends that the answer to that question can be gotten off the shelf. I don’t think that’s true. I think you can’t ask a mess-o-pundits for the answer. First because they aren’t in the trenchs, second because they don’t do a very good job of admitting how everything is in flux, and third because nobody is going to take action of the magnitude that is required in these situations on the advice of outsiders. You have to find a way to get real customer contact and let that drive your adaption.

You gotta go down river. You gotta live in the village emerging around the new bridge. And if at all possible buy one. Not for the usual rolling up market share reasons, but so you can inform your confused self thru direct experiance.

Stanley Kober

Stanley Kober

One obvious way to solve the problem is to have the producer ship the content directly to all N consumers. He pays for N units of outbound bandwidth and each of his consumers pays for 1 unit of inbound bandwidth. The total cost to get the message out is then 2*N. Of course I’m assuming inbound and outbound bandwidth costs are identical. If we assume that point to point message passing is all we’ve got, i.e. no broadcast, then 2*N is the minimal overall cost to get the content distributed.

One obvious way to solve the problem is to have the producer ship the content directly to all N consumers. He pays for N units of outbound bandwidth and each of his consumers pays for 1 unit of inbound bandwidth. The total cost to get the message out is then 2*N. Of course I’m assuming inbound and outbound bandwidth costs are identical. If we assume that point to point message passing is all we’ve got, i.e. no broadcast, then 2*N is the minimal overall cost to get the content distributed. It’s not hard to imagine solutions where the consumers do more of the coordination, the cost is split more equitably, the producer’s cost plummet, and the whole system is substantially more fragile. For example we can just line the consumers up in a row and have them bucket brigade the content. We still have N links, and we still have a total coast of 2*N, but most of the consumers are now paying for 2 units of bandwidth; one to consume the content and one to pass it on. In this scheme the producer lucks out and has to pay for only one unit of band width, as does the last consumer in the chain. This scheme is obviously very fragile. A design like this minimizes the chance of coordination expertise condensing so it will likely remain of poor quality and high cost. Control over the relationships is very diffuse.

It’s not hard to imagine solutions where the consumers do more of the coordination, the cost is split more equitably, the producer’s cost plummet, and the whole system is substantially more fragile. For example we can just line the consumers up in a row and have them bucket brigade the content. We still have N links, and we still have a total coast of 2*N, but most of the consumers are now paying for 2 units of bandwidth; one to consume the content and one to pass it on. In this scheme the producer lucks out and has to pay for only one unit of band width, as does the last consumer in the chain. This scheme is obviously very fragile. A design like this minimizes the chance of coordination expertise condensing so it will likely remain of poor quality and high cost. Control over the relationships is very diffuse. We can solve the distribution problem by adding a middleman. The producer hands his content to the middleman (adding one more link) and the middleman hands the content off to the consumers. This market architecture has N+1 links or a total cost of this scheme is 2*(N+1). Since the middleman can server multiple producers the chance for coordination expertise to condense is generally higher in this scenario. Everybody, except the middleman, see their costs drop to 1. Assuming the producer doesn’t mind being intermediated he has incentive to shift to this model. His bandwidth costs drop from N to 1, and he doesn’t have to become an expert on coordinating distribution. The middleman becomes a powerful force in the market. That’s a risk for the producers and the consumers.

We can solve the distribution problem by adding a middleman. The producer hands his content to the middleman (adding one more link) and the middleman hands the content off to the consumers. This market architecture has N+1 links or a total cost of this scheme is 2*(N+1). Since the middleman can server multiple producers the chance for coordination expertise to condense is generally higher in this scenario. Everybody, except the middleman, see their costs drop to 1. Assuming the producer doesn’t mind being intermediated he has incentive to shift to this model. His bandwidth costs drop from N to 1, and he doesn’t have to become an expert on coordinating distribution. The middleman becomes a powerful force in the market. That’s a risk for the producers and the consumers. It is possible to solve problems like these without a middleman, instead we introduce exchange standards. Replacing the middleman with a standard. Aside: Note that the second illustration, Consumers coordinate, is effectively showing a standards based solution as well. We might use a peer to peer distribution scheme, like Bit Torrent for example. To use Bit Torrent’s terminology the substitute for the middleman is called “the swarm” and the coordination is done by an entity known as the “the tracker.” I didn’t show the tracker in my illustration. When bit torrent works perfectly the producer hands one Nth of his content off to each of the N consumers. They then trade content amongst themselves. The cost is approximately 2 units of bandwidth for each of them. The tracker’s job is only to introduce them to each other. The coordination expertise is condensed into the standard. The system is robust if the average consumer contributes slightly over 2 units of bandwidth to the enterprise, it falls apart if that median falls below 2. A few consumers willing to contribute substantially more than 2N can be a huge help in avoiding market failure. The producer can fill that role.

It is possible to solve problems like these without a middleman, instead we introduce exchange standards. Replacing the middleman with a standard. Aside: Note that the second illustration, Consumers coordinate, is effectively showing a standards based solution as well. We might use a peer to peer distribution scheme, like Bit Torrent for example. To use Bit Torrent’s terminology the substitute for the middleman is called “the swarm” and the coordination is done by an entity known as the “the tracker.” I didn’t show the tracker in my illustration. When bit torrent works perfectly the producer hands one Nth of his content off to each of the N consumers. They then trade content amongst themselves. The cost is approximately 2 units of bandwidth for each of them. The tracker’s job is only to introduce them to each other. The coordination expertise is condensed into the standard. The system is robust if the average consumer contributes slightly over 2 units of bandwidth to the enterprise, it falls apart if that median falls below 2. A few consumers willing to contribute substantially more than 2N can be a huge help in avoiding market failure. The producer can fill that role.