Ben Franklin changes his mind:

I believe I have omitted mentioning that, in my first voyage from Boston, being becalm’d off Block Island, our people set about catching cod, and hauled up a great many. Hitherto I had stuck to my resolution of not eating animal food, and on this occasion consider’d, with my master Tryon, the taking every fish as a kind of unprovoked murder, since none of them had, or ever could do us any injury that might justify the slaughter. All this seemed very reasonable. But I had formerly been a great lover of fish, and, when this came hot out of the frying-pan, it smelt admirably well. I balanc’d some time between principle and inclination, till I recollected that, when the fish were opened, I saw smaller fish taken out of their stomachs; then thought I, “If you eat one another, I don’t see why we mayn’t eat you.” So I din’d upon cod very heartily, and continued to eat with other people, returning only now and then occasionally to a vegetable diet. So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.

The mind is not a particularly consistent thing. I like that: “a reasonable creature” because it is a more modern framing of this puzzle than the classic, i.e. Greek, where in the the rational man does battle with his animal self, typically thru the medium of will power. Franklin is more modern, he reasons cheerfully amoungst his multiple interests.

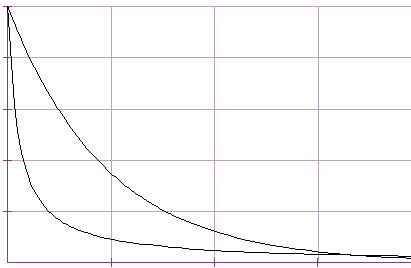

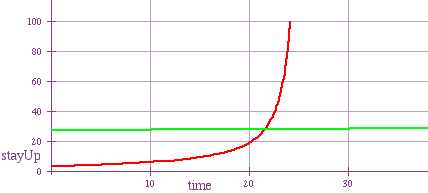

I gather we can now be quite exacting about what’s going on when we change our minds. Below we have two ways that we might weight the value of future rewards. The upper curve is that prescribed by the rational man beloved econ 101 text books. The lower curve is the result of experiments on pigeons, children, and undergraduates.