The 31 people on the cover of Parade magazine’s “What People Earn” issue make an average income of 5.8 Million a year. They over sample the elities and under sample the poor.

Meanwhile I want to rant a bit on Dunbar’s number. Dunbar’s number is nicely explained here. The theory goes that you weight the monkey’s noodle and then you plot that versus group sizes you find a correlation. Humans are on the perimeter of this plot (aren’t we?). If you want to play along then our group size is then around a 150. I guess that might work if we were monkeys.

But we aren’t. Language changes the game. It’s a lot easier to solve coordination problems with a bit of language. Technology changes the game. Rolodex, Outlook, oh and the printing press.

Specialization changes the game. In both the business models that give rise to income and the social models that give rise to group structure humans are pretty clever at finding frameworks that enable them to work around limits that might otherwise put a limit on the upper bounds of these things. The distribution of group sizes, the distribution of social contacts, the distribution of wealth do not appear to be capped by physical limitations. My first problem with Dunbar’s number is that it posits the existence of an upper limit when the data doesn’t seem to show any such limit. For example we don’t see any sign that village/city/nation sizes are capped by some limit.

My second problem with Dunbar’s number is that everything seen of it suggests that its fans are uninformed by the power-law distribution in the underlying data. Which means that they aren’t aware of the extremely skew’d distribution of affiliations in real populations.

Dunbar’s number is a measure of social capital. Social capital, like economic capital is not a zero sum game nor is it uniformly distributed. Reasoning by analogy or on the basis of small samples sets is almost always extremely misleading in the presence of highly skew’d distributions.

The bottom 20% of households in the United states captured 3.4% of the total income. Think about that! Should the same distribution holds for affiliations, and I see no reason to think otherwise, that means that one out of five people participate less than 4% of the the benefits generated by the social fabric.

Parade? It misleads you about the elite portions of the social network and the long tail. So does Dunbar’s number. Parade magazine isn’t pretending to be professional, it’s just trying to sell you mattresses, celebrities, and herbal remedies. Dunbar’s number on the other hand is just, well, wrong.

In a fine example of the revenge of the long tail I picked up this virus at Harvard. At a talk on honor and revenge, no less. I’ve been sick for a week!

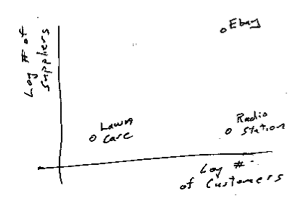

In a fine example of the revenge of the long tail I picked up this virus at Harvard. At a talk on honor and revenge, no less. I’ve been sick for a week! Zooming in on the landscape of the supply chain/graph we can make a very simple model of the firm. The firm has some skills which it plies by drawing inputs from suppliers and creating outputs for it’s customers. For example a lawn mowing business. On the supplier side a few employees, equipment suppliers, insurance, accountant, a bank, maybe a phone. On the customer side maybe a hundred customers. Not too much skill; mostly the skill of keep all these relationships functioning.

Zooming in on the landscape of the supply chain/graph we can make a very simple model of the firm. The firm has some skills which it plies by drawing inputs from suppliers and creating outputs for it’s customers. For example a lawn mowing business. On the supplier side a few employees, equipment suppliers, insurance, accountant, a bank, maybe a phone. On the customer side maybe a hundred customers. Not too much skill; mostly the skill of keep all these relationships functioning. Then there are firms with huge numbers of suppliers and customers. A fast food restaurant chain for example has lots and lots of employees, real estate deals, local legal & political connections, on the supply side along with numerous customers on the other. Or consider eBay with it’s huge pool of sellers who supply it with goods and it’s huge pool of buyers who receive those goods. Or consider Google with its huge pool of content providers v.s. its pool of eyeballs searching for goods.

Then there are firms with huge numbers of suppliers and customers. A fast food restaurant chain for example has lots and lots of employees, real estate deals, local legal & political connections, on the supply side along with numerous customers on the other. Or consider eBay with it’s huge pool of sellers who supply it with goods and it’s huge pool of buyers who receive those goods. Or consider Google with its huge pool of content providers v.s. its pool of eyeballs searching for goods.

Between producers and consumers you need to insert some sort of exchange, a trusted intermediary. I’ve always liked the way that people draw this as a cloud. It suggests angels are at work, or possibly that if you look closely things will only get blurry and your glasses will get wet. Even without getting your self wet things aren’t clear even from the outside. For example what do we mean by trust? Does it mean low-latency, reliability, robust governance, low barriers to entry, competitive markets, minimal concentration of power – who knows?

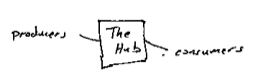

Between producers and consumers you need to insert some sort of exchange, a trusted intermediary. I’ve always liked the way that people draw this as a cloud. It suggests angels are at work, or possibly that if you look closely things will only get blurry and your glasses will get wet. Even without getting your self wet things aren’t clear even from the outside. For example what do we mean by trust? Does it mean low-latency, reliability, robust governance, low barriers to entry, competitive markets, minimal concentration of power – who knows? There are some leading design patterns for working on these problems. Sometimes the cloud condenses into a single hub. For example one technique is to introduce a central hub, or a monopoly. The US Postal system, the Federal Reserve’s check clearing houses, AT&T’s long distance business are old examples of that. Of course none of those were ever absolute monopolies; you could always find examples of some amount of exchange that took place by going around the hub – if you want to split hairs. Google in ‘findablity’, eBay in auctions, Amazon in the online book business are more modern examples.

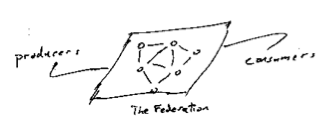

There are some leading design patterns for working on these problems. Sometimes the cloud condenses into a single hub. For example one technique is to introduce a central hub, or a monopoly. The US Postal system, the Federal Reserve’s check clearing houses, AT&T’s long distance business are old examples of that. Of course none of those were ever absolute monopolies; you could always find examples of some amount of exchange that took place by going around the hub – if you want to split hairs. Google in ‘findablity’, eBay in auctions, Amazon in the online book business are more modern examples. Federated approachs are clearly more social than hubs. In markets where the participants are naturally noncompetitive they can be quite social. For example when national phone companies federate to exchange traffic, or small banks federate to clear checks or credit card payments. That can change over time, of course. The nice feature of a federated architecture is that it helps create clarity about where the rules of the game are being blocked out. How and who rules the cloud is part of the mystery of trust.

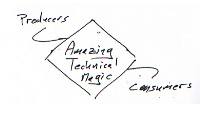

Federated approachs are clearly more social than hubs. In markets where the participants are naturally noncompetitive they can be quite social. For example when national phone companies federate to exchange traffic, or small banks federate to clear checks or credit card payments. That can change over time, of course. The nice feature of a federated architecture is that it helps create clarity about where the rules of the game are being blocked out. How and who rules the cloud is part of the mystery of trust. The magic based solutions have great stories or illustrations to go with them. For example the early Arpanet architecture had each node in the net act advertise it’s service to it’s neighbors who would then shop for the best route – boy did that not work! I worked on on three multiprocessors in the 1970s that had varing designs for how to route data between CPU and memory. One of these, the Butterfly, had a switched who’s topology was based on the Fast Fourier Transform.

The magic based solutions have great stories or illustrations to go with them. For example the early Arpanet architecture had each node in the net act advertise it’s service to it’s neighbors who would then shop for the best route – boy did that not work! I worked on on three multiprocessors in the 1970s that had varing designs for how to route data between CPU and memory. One of these, the Butterfly, had a switched who’s topology was based on the Fast Fourier Transform.

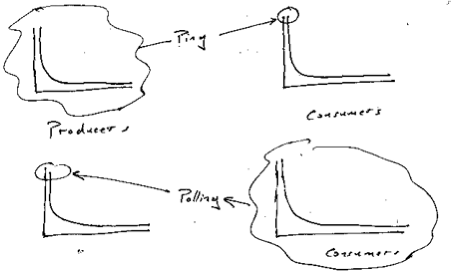

when they have fresh content. This is sometimes called the Ping problem. Sometimes it’s called push, to contrast it with the typical way that content is discovered on the net i.e. pulling it from it’s source. The problem interests me for an assortment of reasons, not the least of which is that it’s a two sided network effect. On the one side you have writers and on the other side you have readers. I draw a drawing like the one on the right for situations like that. Two fluffy clouds for the producers and the consumers connected thru some sort of exchange.

when they have fresh content. This is sometimes called the Ping problem. Sometimes it’s called push, to contrast it with the typical way that content is discovered on the net i.e. pulling it from it’s source. The problem interests me for an assortment of reasons, not the least of which is that it’s a two sided network effect. On the one side you have writers and on the other side you have readers. I draw a drawing like the one on the right for situations like that. Two fluffy clouds for the producers and the consumers connected thru some sort of exchange.