Some people pick a question, usually in graduate school, and then spend the rest of their life puzzling out an answer to that question. Lately I’ve been reading some of Irving Janis‘ work on decesion making. The question he seems to have asked early on was “How did these smart people make those choices that lead to this fiasco!” In his book Groupthink he looks at the fiasco of Pearl Harbor, the crossing into North Korea in the Korean war, the Bay of Pigs, and the escalation in Vietnam.

This turns out to be an excellent question to build a career around! No shortage of fiascoes to study. No shortage of people with money scared to death they are on the road to a fiasco. Better yet there is no shortage of people convinced that those around them are on that road.

Making a decision is embedded in a context that aids and constrains the outcome that gets generated. This cartoon highlights three aspects of the context. In this view of the problem solving we ignore the actual problem and look only at the resources brought to bear on solving it.

Irving establishes a straw-man he calls “Vigilante Problem Solving.” That’s the good kind of problem solving and it outputs good decisions. The failure modes are framed as “taking short cuts” or other resource limits that preclude the good kind of problem solving.

Here’s a little enumeration of constraints on the quality of the problem solving that lifted from his book Critical Decisions along those three dimensions.

- Cognitive Constraints

- Limited Time

- Perceptions of Limited Resources

- Multiple Tasks

- Perplexing complexity of the issue

- Perception of lack of knowledge

- Ideological Commitments

- Need to maintain: power, status, compensation, social support.

- Need for acceptability of new policy with organization

- Strong personal motive: Greed, Desire for fame, etc.

- Arousal of an emotional need: e.g. anger, elation

- Emotional stress of decisional conflict

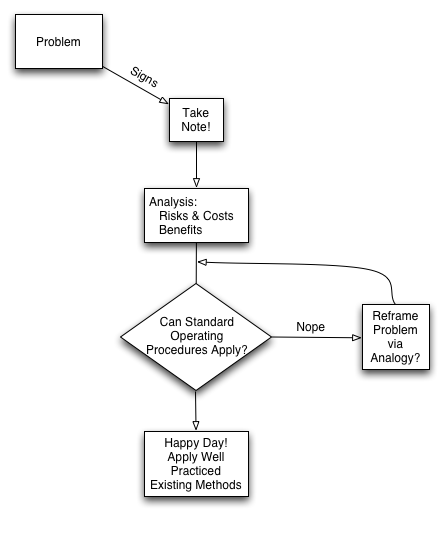

The constraints lead to failure modes. By picking apart the historical record of the various fiascos he has collected a library of these failure modes. The contribution of the Critical Decisions book bridge between the model of resource limits and various failure modes. It’s a bridge from a general model to the stories in his collection of fiascos. Each bridge is a template that outlines a given problem solving technique and then highlights how that problem solving technique goes bad.

Here’s an example. A template for a problem solving technique that plays to a person or organization’s strengths an augments those with reasoning by analogy:

We have cliches to dis this technique. “Searching where the light’s bright.” of “If you’ve got a hammer everything looks like a nail.

But this is a fine problem solving scheme. We all use it. It plays to our strengths and let’s us leverage our organizational muscle. It will only lead to a fiasco if the problem fails to fit the available SOP. Things fall apart when the organization starts getting highly invested in the analogy between a nail and screw. Then they start engaging in various thought stopping processes and begin singing in unison: “I gotta hammer, I hammer in the morning…” For a while they think they are happy!

Vigilance is hard work.

While interpreting “decesion making” as “decession making” makes for interesting analogies, I think you meant “decision making” actually. Nice thoughts. 🙂

That sounds like an interesting book! I put it on my wishlist. If you like this stuff, you might be interested in “The Logic of Failure,” which looks at decisionmaking and has a number of fascinating case studies — including one of the Chernobyl meltdown.

Pingback: Sam Ruby