I got an Onion of the day calendar for Christmas and this gem from 2002 came up recently.

U.S. Middlemen Demand Protection From Being Cut Out

WASHINGTON, DC-Some 20,000 members of the Association of American Middlemen marched on the National Mall Monday, demanding protection from such out-cutting shopping options as online purchasing, factory-direct catalogs, and outlet malls. “Each year in this country, thousands of hard-working middlemen are cut out,” said Pete Hume, a Euclid, OH, waterbed retailer. “No one seems to care that our livelihood is being taken away from us.” Hume said the AAM is eager to work with legislators to find alternate means of passing the savings on to you.

The classic paper by Saltzerz, Reed, and Clark End-to-End Arguments in System Design which gave rise to the stupid network is principally about how to expend your design resources. It argues that your communication subsystem needn’t address a range of seemly necessary functions: bit recovery, encryption, message duplication, system crash recovery, delivery confirmation, etc. etc. This is a relief for the system designer, he can ship earlier.

The end-to-end principle drove a lot of design thinking for the Internet. For example DNS, the mapping of names to IP addresses, is layered above UDP, which is above IP. The end-to-end principle drove DNS up the stack like that.

The designer in the thrall of the end-to-end principle strives to leave problems unsolved. That makes it a kind of lazy evaluation technique. Leaving problems for later increases the chances the will get solved by the end users rather than by the system designer. It pushes the locus of problem solving toward the periphery. It creates option spaces for third party search, innovation, etc.

It is possible to look on the design principle as shifting risk. By leaving the problem resolution to later the design is relieved of the risk that he will screw it up. While users might prefer to have their problems solved by some central authority they do get a bundle of benefits if the problem is handed off to them. These benefits are otherside of the coin of agency risks.

The end-to-end principle is always about managing the risk associated with agency. The Internet’s designers were well aware that they were attempting to create a communication subsystem that would remain open, robust, and hard to capture. Those goals were complementary with designing a system that could survive in battle.

When ever you clear the fog around one of these communication or distribution networks you find a power-law distribution. I.e. you find hubs. I.e. you find middlemen. I.e. you discover the risks of agency.

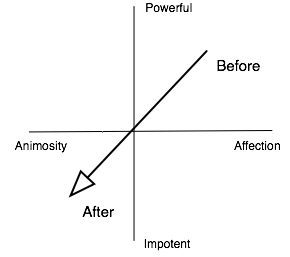

I don’t think that the original designers of the Internet expected to see the concentration of power we see in Internet traffic, domain name service, email, instant messaging, etc. etc. Nor do I suspect they expected to see the concentration of power that the internet has triggered in the industries that are moving on top of it; i.e. a single auction hub, a handful of payment hubs, a single world wide VOIP hub, an handful of book distributors, a handful of music distributors, one browser, one server, etc. etc.

Nothing in the end to end principle actually frustrates that outcome. It argues that there are a collection of reasons why a middleman, i.e. designer of a distribution/communication cloud, might find it advantagous to limit what functions he preforms in his role as intermediary. It doesn’t argue that intermediaries shouldn’t exist. The middlemen in the Onion piece are not being displaced by other middlemen. Middlemen rarely disappear completely.

This is why it is an ongoing effort to keep the network open. While we have a bag of tricks for shifting problems toward the edges and out of the center we seem largely at sea about how to control the degree to which hubs condense on the layers above us.

Stanley Kober

Stanley Kober  Artist trading cards are the size of a baseball card. Artists make them to trade with each other. Some are just

Artist trading cards are the size of a baseball card. Artists make them to trade with each other. Some are just