Here’s something I found very thought provoking:

Here’s something I found very thought provoking:

“So far as I can determine, no demonstration ever occurred anywhere in the world prior to 1760.”

That’s from Tilly’s book on violence; he goes on to say that the demonstration quickly spread as a common form of political action in the following century.

So it appears the demonstration is an invention that emerged in tandem with the modern democratic state. Which makes perfect sense in Till’s model of violence. I.e. that only high functioning democratic states can sustain a large range of political activities while at the same time avoiding contentious violence emerging from those activities. Of course a strong state that’s not democratic proscribes such activities – in fact in some points in history the authorities would have to officially set aside the law against assembly on market days. A weak democratic state might allow them; but they run a much higher risk of that they will turn violent.

In Tilly’s model any given society provides both assorted means affecting changes to the status quo and it forbids other ways.

- Forbidden – for example just taking what you want.

- Tolerated – making a petition to the king.

- Contentious – public debate, violent demonstrations

- Proscribed – for example the electoral process is highly proscribed.

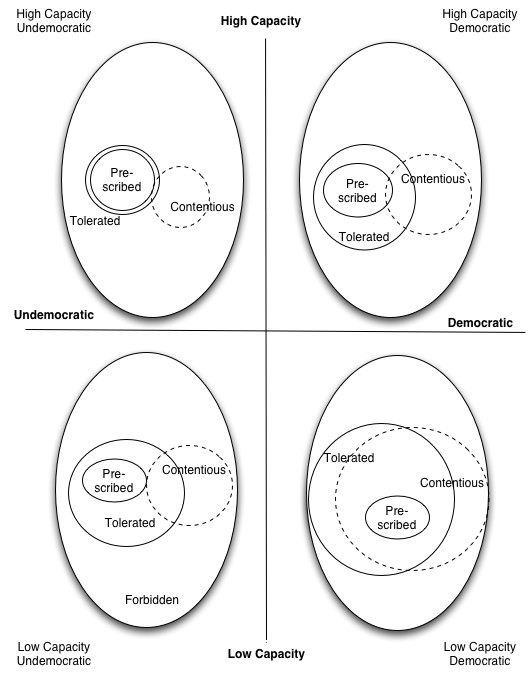

Contrast these to two measures of state structure: capacity v.s. democratic. Tilly has this fun drawing that attempts to show how four kinds of states portion out the amount of what is tolerated, proscribed, and contentious. For example this drawing suggests that elections are more likely to be contentious in low capacity democratic state.

He doesn’t explicitly build the linkages between his curious historical fact about demonstrations and the model illuminated by that drawing. But let’s try. A demonstration is an activity right on edge of contentious, just barely tolerated, but so ritualized as to be almost proscribed. A demonstration is more likely to occur if you have a larger sphere of tolerated activities. You less likely to have the demonstration explode into a riot of violent contentious activity the smaller the sphere of contentious activities. Demonstrations are actually surprisingly ritualized; as we shall see in a moment, so the larger the prescribed sphere the better. All of these suggest that a demonstration is most likely to pop-up in a highly democratic state; but it also suggests what is likely to happen if it pop’s up in any of the other quadrants.

A state that lacks the capacity to regulate things will find that it has to tolerate a large range of activities, can proscribe only a few things and sadly it will host lots of highly contentious activities. A democratic state will strive to tolerate more and it will tend to provide a larger range of alternative, but proscribed, means of achieving your ends. Thus it appears that only as high functioning reasonably democratic states began to emerge that demonstrations became tolerated, and the means to proscribe them emerged that could avoid their becoming highly contentious.

It helps to think about example like Iraq, India, China, Massachusetts. For example I’m very impressed by the response in Spain to the recent bombings.

Demonstrations are surprisingly ritualized; a kind of a hybrid of the procession and the petition. He provides a nice concise definition of the beast: A) Gathering deliberately in a public, visible, and often-symbolic place, that B) displays membership in a politically relevant constituency so as to C) presenting a position on an issue; typically via voice, words, and symbolic objects; in a manner that D) proves by acting in a disciplined manner the group’s determination, and coordination (hence the marching).

He even provides a scorecard: Worthiness, Unity, Numbers, and Commitment to get a sense of the scale of a demonstration. “Five prisoners rhythmically beat their cups on the lunch room table before desert was served.” just isn’t as awe inspiring as “Four thousand veterans marched on the capital to spend the week lobbying.”